Besides pursuing a career in architecture, Lawrence Buttigieg (PhD, Loughborough University, UK) is also an artist and freelance researcher. The recurrent theme of Buttigieg’s studio-work and research is essentially the representation of womanhood. He creates box-assemblages through which his association with the female subject is taken to an acutely intense level. By means of these artworks Buttigieg examines concepts of alterity and selfhood, and challenges the dominant role of male subjectivity in the western world.

Pros-thesis

A research film on artefactual prosthesis. Our shared necessity to come together and create the box-assemblage disputes the utopian myth that our bodies are complete and self-sufficient entities.

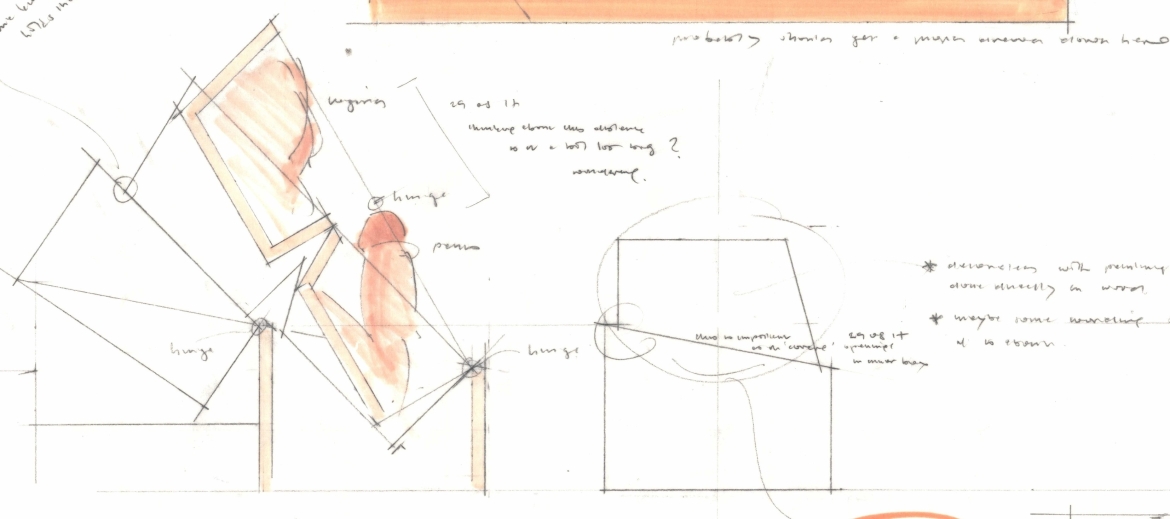

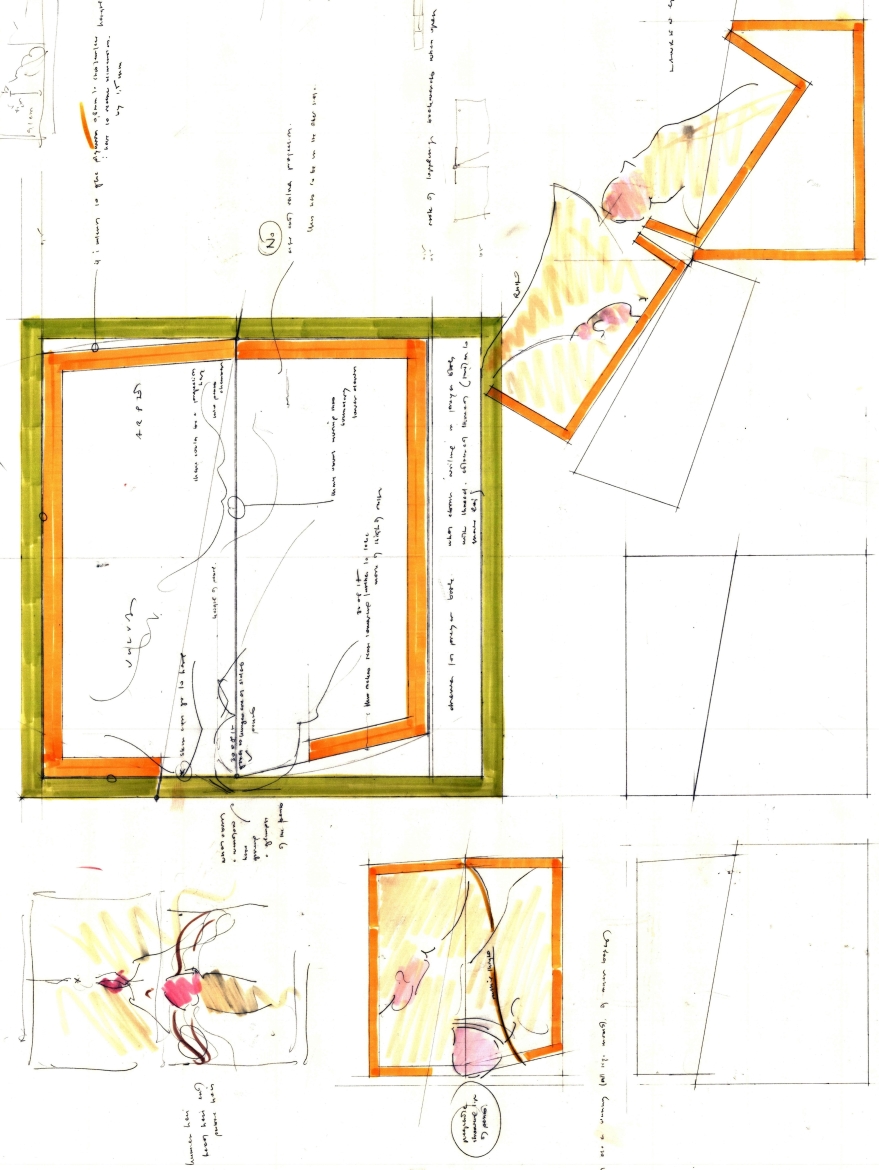

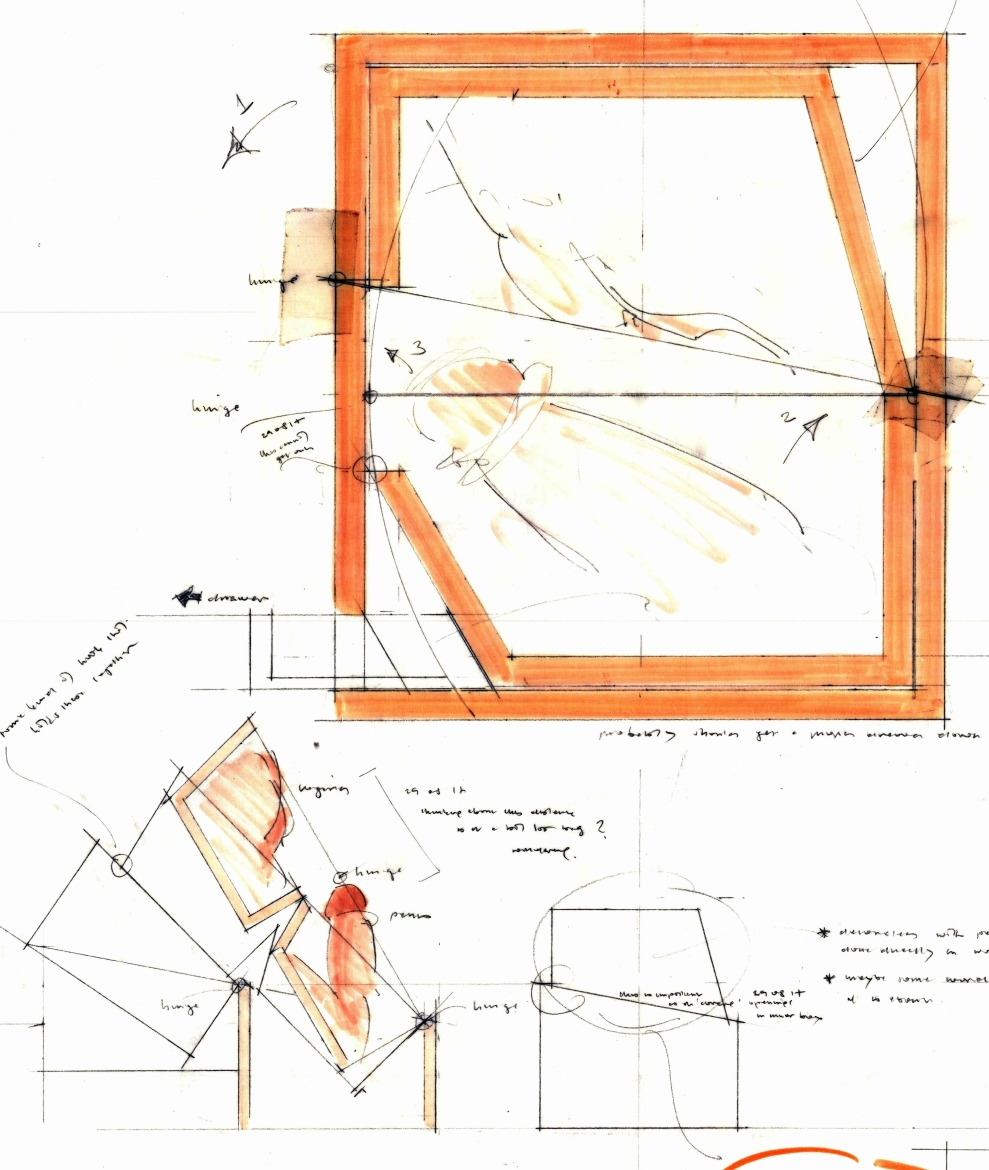

Pros-thesis is an experimental research film that hinges on the box-assemblage, a three-dimensional, mixed-media, body-themed artefact, whose creation depends on a number of processes necessitating a strict collaboration between Cesca[1] and myself. It starts off by tracing the artefact’s inception to the confines of my studio where an ‘intimate’ encounter takes place between two ‘bodies that matter’—a phrase borrowed from Judith Butler’s book title to stress our distinct corporeality, rather than our semantically gendered occupations of female model and male artist; more than anything else, what ‘matters’ is our material substance and complementary intelligibility (Butler 1993: 7). Then, taking advantage of the medium’s inherent potential of contiguity, the film continues its chronicle by linking signs, establishing associations, and mapping out salient episodes affecting the creation of the artefact through space and time.

Through studio-based narratives, Pros-thesis shows that although as embodied selves we generate our own independent thoughts and feelings, the physical closeness and mutual affection spawns concepts of convergence and assimilation that seek and nurture their own self-sufficiency through an independent existence. While inventiveness permits us to conceive such an actuality, shared earnestness to apperceive the alterity embodied by each other, impels us not only to draw up its blueprint, but to commit ourselves to its manufacture with all the creative processes and meticulous labours involved. Pros-thesis documents how Cesca and myself work hands-on, or practically, with a variety of stuff to make it happen; in doing so it examines the manifold sensations, correlations, and understandings that we experience when engaging our bodies with the distinct corporeality of materials, implements, and objects.

The film underscores the intensity of such an engagement when it comes to silicone, the primary material we use in the manufacture of facsimiles of our body fragments. While revealing how the uncured polymer is gently daubed across our skin and pushed into crevices and creases, Pros-thesis affirms that the powerful sensations generated by its viscousness and adhesion are consonant with Didier Anzieu’s notion of the skin-ego. The curing of the material against our flesh not only excites our whole being but seems to concentrate it on the shared interface; ‘consensuality,’ the confluence of all senses at this point of contact, characterises the whole process. Furthermore, the motion picture illustrates how the gradual unfolding of this activity strongly attests to Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s assertion that the act of touching involves a binary sensation, namely that of feeling and being felt; the interface between skin and silicone translates into our point of exchange and transmission. Starting off as two distinct viscous products without identifiable surfaces, once cured the silicone registers the obverse of our anatomies; capturing the palpability and nuances of the skin, these moulds make possible the near-perfect replication of our body-parts (Merleau-Ponty 1964: 141; Segal 2008: 6).[2] With this and similar examples, Pros-thesis goes on to demonstrate that the manufacture of the box-assemblage not only brings us ponderably, and even corporeally, closer to each other, but also effects the subjective objectification of ourselves through each other, or what Elaine Scarry subtly defines as the condition of ‘self-displacing, self-transforming objectification’ (Scarry 1985: 166). Pros-thesis claims the box-assemblage is in essence all about two persons coming together to mutually enrich each other’s experience of carnal embodiment, the state of being eloquently described by Vivian Sobchack as ‘…the lived body as, at once, both an objective subject and a subjective object: a sentient, sensual, and sensible ensemble of materialised capacities and agency that literally and figurally makes sense of, and to, both ourselves and others’ (Sobchack 2004: 2).

Intimating that the box-assemblage not only embodies Cesca and myself but externalises our ‘awareness of aliveness’ (Scarry 1985: 289), Pros-thesis hints that as an object of our creation, it is not just the materialisation of our existential selves but the exteriorisation of our sentient consciousnesses and, accordingly, our capacity for becoming and re-inventing ourselves through ‘self-replication and self-modification.’ Together we not only transform it into a sanctum for our beings, our feelings and our desires, but also into a prosthesis of our paired bodies.

By way of an interplay of revealing and concealing through temporal space, the film prompts the viewers to push their perception beyond that which is straightforwardly obvious. Instead of adhering to an anecdotal and linear kind of narrative, the moving image resorts to pertinent scenes and dialogues, juxtaposed in such a manner that engages the partakers in multivalent kinds of looking and listening that go beyond the accustomed and unimaginative.

While the sequence of divulged circumstances on the two-dimensional luminescent plane are significant enough, they allow interstices through which the spectator may glimpse unchartered territory, that which is liminal and subject to interpretation. Embracing this style, the motion picture metamorphoses into the viewers’ very own visual-prosthesis, the kind that prompts them to mnemonically draw their own associations and seek new understandings, especially when it comes to Cesca with whom they are linked through technological paraphernalia.

While the camera lens and the luminescent plane of the screened film are two distinct elements, they very well constitute a single interface. Although physically apart, they are hooked up through a complex conglomerate of contrivances, both analogue and digital, assembled and controlled by human knowledge. Cesca is aware that the cinematograph set up in the studio is an optical and audio device that captures and registers her actions. She is also mindful that the data being collected is electronically dispatched across the globe and transformed into a structured motion picture whose audience is broadly anonymous but may also include family members, close friends, and acquaintances. Notwithstanding all this, Cesca confidently engages the camera lens with her gaze while lending her unclad body to the creative process. While Cesca’s nakedness connotes vulnerability, her facial expression and demeanour suggest otherwise.

Fast-forward through time and space, Pros-thesis’s spectators experience the uncanny sensation that Cesca is looking at them even though they are corporeally absent. Transposing and interpreting Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s understanding of the gaze as ‘flesh,’ this moving image underscores the significance of the lens/film-plane interface as the site where the gaze of Cesca and that of her viewers interconnect. Self-reflexively, it also goes on to show that this technical juncture embodies Merleau-Ponty’s concept of ‘chiasm,’ that which ontologically stands for the intertwining of the body’s interiority with its exteriority, and the consequent enfleshment of the latter (Merleau-Ponty 1964: 138; 214-5).

Self-reflexively, Pros-thesis draws on the intriguing ideas of David Wills to connote that its creation doubles as a process of recontextualization of Cesca and myself since, from the very instant of its conception, it renders us an ancillary existence through its prosthetic attributes (Wills 1995: 46). Wills contends that any prosthesis sets in place a ‘prosthetic network’ with the power of prosthetising whatever and whomever it relates to. Through its own reticulation, this film not only takes hold of our personae, and anyone who wishes to participate in our rendezvous, but imbues us with its otherness, establishes between us a relationship of difference, and brings about our division, or rather pluralisation (Wills 1995: 46). Pros-thesis concludes with a direct reference to Wills’ observation that the complementariness between this pluralisation and otherness is evocative of Luce Irigaray’s observation that a woman as other is essentially always two rather than one, on account of her two labia which are always in contact and readily caressing each other (Wills 1995: 44; Irigaray 1985: 24).

Pros-thesis notes

I am confident that Pros-thesis will encourage viewers to adopt critical modes of perception and join us in our quest to address and fathom the complex and ambiguous nature of alterity.

Other points that may be addressed by Pros-thesis

Flux, fluidity, fixity: Ovid’s Myth of Apollo and Daphne

Cesca’s relationship with her own body

'Cesca, detail (2017) - unfinished, oil on canvas, 195 x 130 cm

'Cesca, detail (2017) - unfinished, oil on canvas, 195 x 130 cm

Cesca’s and Lawrence’s engagement with the unknown viewer

Cesca’s communication with her viewers through her sex,

just like the anonymous woman in Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde, 1866

The luminescent plane of the film as flesh

The relationship between Cesca’s flesh and ‘things’

Cesca’s own thoughts about replicating herself through the box-assemblage

The intertwining of bodies, materials and things

The permeability of the body

Cesca reminiscences about her experiences in the studio:

As much as my body seems to be so ordinary, when engaged with you and the project in hand, I become conscious of its uniqueness and inherent power to inspire.

I become hyper-sensitive when it comes to taking moulds off my skin. At such instances I am truly aware of what it means to live one’s own body, that is in the flesh.… And then there’s the excitement of examining replicas of my own sex. Probably, it’s the only experience that permits me to truly appreciate with wonder the physicality of my vulva, its uniqueness of form, complexity, inherent beauty, and sensuality—I’m always pleasantly surprised. And then there’s the satisfaction of knowing that parts of my body are being preserved in time….

References

Butler, Judith. Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of sex. New York: Routledge. 1993.

Garoian, Charles R. The prosthetic pedagogy of art: Embodied research and practice. New York: State U of New York P. 2013.

Harris, Anne M. Video as method: Understanding qualitative research.

Heath, Christian and Dirk vom Lehn. ‘Configuring reception (dis-)regarding the “spectator” in museums and galleries.’ In Theory, culture and society. SAGE. Vol 21(6), pp 43-65.

Irigaray, Luce. This sex which is not one. Trans. Porter, Catherine. Ithaca, New York: Cornell U P. 1985.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. ‘Eye and mind.’ In James Edie. Ed. The primacy of perception. Evanston: Northwestern U P. 1964.

_ _ _ and Thomas Baldwin. Maurice Merleau-Ponty. London: Routledge. 2004.

_ _ _. The visible and the invisible. Evanston: Northwestern U P. 1968.

Scarry, Elaine. The body in pain. Oxford U P. 1985.

Segal, Naomi. Consensuality: Didier Anzieu, gender and the sense of touch. Editions Rodopi BV. Amsterdam. 2008.

Sobchack, Vivian. Carnal thoughts. Berkeley: U of California P. 2004.

Wills, David. Prosthesis. Stanford U P. Stanford, California. 1995.

[1] Cesca is an alias that refers to more than one person.

[2] In addition plaster is used to secure the shape of the cured silicone.

Film shots from Pros-Thesis:

Click HERE for the sensual avant-garde experiments of the Czech photographer František Drtikol...!!

Below you can check out the complete film...

More of Buttigieg's art can be found on his site....!!

An extensive treatise on Buttigieg’s Box-Assemblages can be found in the following PDF…..!!

If you have any questions or want to let us know your thoughts on Buttigieg's work leave your reaction in the comment box below....!!