Almost everyone knows Hokusai‘s iconic The Great Wave and Kuniyoshi‘s robust tattooed Suikoden Heroes or the excellent female close-up portraits (okubi-e) of Utamaro but few will realize that these great Japanese artists also produced shunga, a genre within ukiyo-e that displays the erotic secrets of ancient Japan.

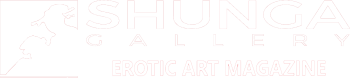

Fig 1. The masterpiece ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (c.1814)’ from the series ‘Young Pine Saplings (Kinoe no komatsu)‘ by Katsushika Hokusai

This article aims to give a comprehensive introduction to the genre and will cover all the relevant topics, Including its history, its bizarre themes and customs, the most important artists of the genre, its aesthetics and at the end we’ll conclude with some collecting tips…

What are the Roots of Shunga?

The fascination for human sexuality is universal and has been a central theme within art from the earliest times. It dates back at least to ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome and throughout the world, from China and India to South America. Erotic art in Japan is as ancient as Japanese art in general. Clay dolls of naked men and women have been found in excavations dating back to the Jomon period (c.14,500-300 BC). During renovations at the Horyu-ji Temple in Nara they discovered phallic paintings from the eighth century.

This explains the liberal attitude towards sexual imagery that was already developed at an early stage of Japanese culture. It is also expressed in early Japanese literature such as the classic The Tale of Genji that was written by Lady Murasaki (c. 973–c. 1014). Scenes from this tale would often appear.

Izanagi and Izanami

A sexual component can also be found in the classical Japanese foundation myth, which tells how the deities Izanagi and Izanami (see Fig.2.) created the islands of Japan. As they stood together in the sky, Izanagi shook his jewelled spear (symbolizing masturbation), and the drop that fell from it into the sea (symbolizing the vagina) created the first Japanese island.

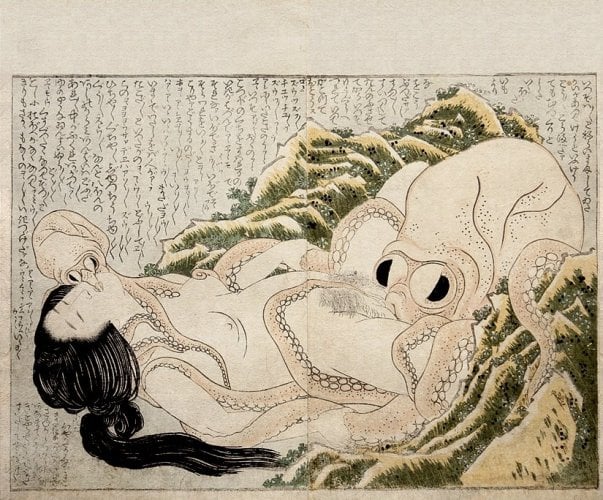

Fig.2. ‘Izanagi and Izanami‘ (c.1823) from the series ‘Makuro Bunko (literally: Pillow Collection)‘ by Keisai Eisen

Later, influenced by observing wagtail birds mating, Izanagi and Izanami created the other Japanese islands by having sexual intercourse. This legend stands at the base of Shinto, the traditional religion of Japan. Even to this day, Shinto shrines occasionally feature fertility gods in the shape of male or female genitals, and participants in Shinto festivals and processions carry objects of devotion shaped like gigantic male organs through the streets.

In the Edo period (1603-1868), the peak of the production, and from long before, paintings usually took the form of makimono (scrolls). These kind of scrolls were painted by hand using mineral pigments, sometimes with added gold or silver, applied on paper or silk. The earliest ‘surviving’ example is a painted erotic scroll called ‘The Phallic Contest (Yobutsu kurabe)’.

It was made by Toba Sōjō (1053-1140) and it features ecstatic women judging men endowed with gigantic penises. In the subsequent orgy, the women clearly are more than a match for the men, who eventually crawl away totally exhausted by their demands. Unfortunately, this scroll painting has been lost and is only known in copied form by means of a 19th century painting.

Meaning of the word Shunga

Nowadays, the most common Japanese name for erotic drawings and prints is shunga, or ‘spring pictures’. This is because many prints portray sexual acts taking place in springtime. Therefore a recurring theme within the genre is the portrayal of cherry blossoms: in Japan these can symbolize the short life span of female beauty, which is the reason why pleasure quarters were decorated with them. Spring is also the season of planting and thus connected to fertility.

Less common names include shunpon (‘Spring books’), enpon or kōshokubon (both translated as ‘amorous books’), mukara-e (‘pillow pictures’), sometimes they were kept in the drawer of a wooden pillow, and higa (‘secret pictures’), which speaks for itself. Another name is abuna-e (‘risky pictures’) that usually applied to images that were more suggestive of sex but did not depict it openly (see Fig.3.).

Fig.3. ‘Sensual liaison‘ (c.1827) from the series ‘Kamigata koi shugyo‘ by Utagawa Kunisada

Occasionally erotic pictures were also called warai-e (‘laugh pictures’), because many of them had a satirical undertone and were used for amusement and entertainment. Also in the Edo period slang the word ‘laugh’ meant masturbation.

Erotic picture books might also plainly be called e-hon which normally meant ‘picture books’ but written with characters that meant ‘erotic books’. The characters used may also be pronounced as haruga. This word is borrowed from China and Korea, where erotic art was also very popular.

Educational

It is often been addressed that these prints had an educational function. Serving as an instructional guide for young newlywed girls on how to perform in bed and fulfill a man’s desires. This did not apply to the young girls in the pleasure quarters, however, who did not need graphic instructions. They were taught the secrets of sexual pleasure and how to act when alone with their clients by oral transmission from experienced courtesans. Actually, they were intended for the people outside the pleasure quarters and were not specifically fashionable within the Yoshiwara.

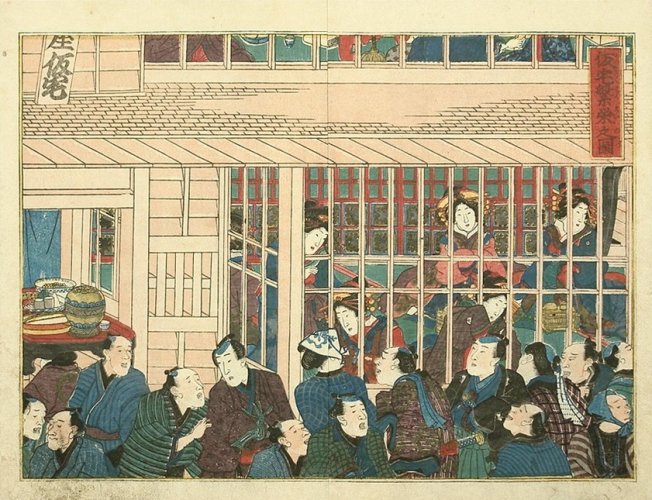

Fig.4. ‘Inside the Pleasure Quarters with courtesans on display for male passersby’ (c.1840s). Untitled series. Attributed to Utagawa Kunisada

Video on “The Yoshiwara”:

Shunga as Merchandise

The march of shunga commenced simultaneously with that of the rise of the Tokugawa period around 1600. Edo (nowadays Tokyo) was chosen by the Tokugawa shogunate as the seat of the government. The Tokugawa society was divided in four classes: the noble samurai of the warrior class held the highest rank, followed by the farmer, then the artisan and craftsman and lastly, the contemptible class in the eyes of the samurai, the merchant (shi–nō–kō–shō).

After 1635 all daimyo (feudal lords) compliant to the Shogun were forced to spend every other year in attendance in the capital Edo, seperated from their wives and families. When in Edo, the daimyo spent their money freely. These levels of consumption led to an explosion in construction and production in Edo, attracted an ever-increasing chōnin (merchant and artisan) community. Although many chōnin became extremely wealthy, their place at the bottom of the social hierarchy meant they were excluded from aristocratic society.

For this reason they sought to create their own cultural identity, an arty urban culture of the Kabuki theatre, light-hearted literature, the popular arts and paid sexual entertainment at licensed and unlicensed pleasure quarters. When the economy changed, and rice was replaced by money as a commercial medium, the merchants became the nouveau riche and were keen to show off their newly acquired wealth.

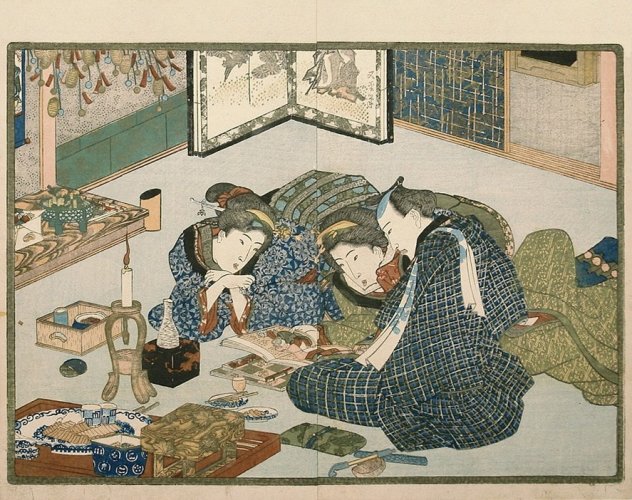

Fig.5. ‘Couple watching erotic scroll ‘ (c.1827) from the series ‘Shunka shuto shiki no nagame (Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter: Prospects for the Four Seasons)‘ by Utagawa Kunisada

The rise of Edo not only had an impact on entertainment forms like the theatre and the pleasure quarters, it also resulted in an increased demand for literature. This ranged from traditional classic tales, contemporary fiction (kana-zōshi) and the much sought after books on the world of love (kōshoku-bon) which also included erotic illustrations and would eventually develop into the genre. Naturally, these books were highly in demand by chōnin.

How were Shunga distributed?

There’s a lot of evidence that during the Edo period these prints and books were distributed. In the autobiography Gyokuen sowa (1902) of the publisher and bookseller Miki Sasuke (1852-1926) he reminisces of the time that shunga circulated with relative freedom throughout most of the Edo period. From time to time there was some censorship on such material but the circulation largely remained the same until the Meiji period (1868-1912). Miki explains: “[…] It was after the Meiji government was established that all this came to a halt and we ended up burning all the blocks we possessed.”

Further evidence of the circulation is that there are many images that depict men and women of all ages and social environments taking pleasure in the reading of erotic books (see Fig.6.) and then the sexual activity provoked by this reading. They also appear as a part of daily life in Edo-period comical senryu poems and can be found in some of the collections accumulated by intellectuals of the Edo period. In other words, shunga spread throughout Edo-period culture, which was only possible because of the easy distribution of this material among potential readers.

Fig.6. ‘Sexual education‘ (c.1837) from the series ‘Sumagoto‘ by Utagawa Kunisada

Readers could gain access through book and print shops. Erotic products formed an important part of their stock and were normally displayed in the shop along with a variety of other products. Another option for shunga lovers were the commercial book-lenders. Compared to bookshops, book-lenders were specifically attractive because they offered a convenient service. First of all, the books were brought by agents directly to the homes of their clients, carrying them in wooden boxes or wrapped in large cloths. So it was very easy for customers to comfortably look through the books in complete privacy. Secondly, the option to borrow books instead of buying them allowed access to expensive richly illustrated prints, for those who could not afford to buy these editions.

The circulation of shunga was further enhanced through ‘human networks’. They were often used as gifts for the upper class, and also as souvenirs of Edo. Publisher-booksellers freely produced them and facilitated their distribution by means of countrywide cataloques until the genre was banned in 1722. By the mid-eighteenth century it had resumed and continued with only minor interruptions to the end of the Edo period in 1868. Because the insatiable appetite for erotic books did not stop the booksellers were prepared to risk official displeasure in order to make a nice profit.

Unveiling Your Passion: Erotic Aesthetics Redefined

Erotic Aesthetics Redefined

Digital magazine for Bold art lovers

If you like this article you will surely like our eBook on Hokusai. Join us and get it for free.

What kind of themes were treated in Shunga?

There is probably no subject found in ukiyo-e that does not appear in shunga. What´s so distinguishing is that it expresses the different aspects of it, mostly in the form of parody. Below the most common themes within the genre will be discussed.

Voyeurism

Voyeurism (Fig.7) is often represented through images in the background of people spying. Through the washi walls and doors (shoji) the sounds made by intimate couples could be overheard, while their shadows revealed their movements. They could also be spied on by peeping through a tiny slit or hole (which recalls the old Japanese saying ‘the walls have ears, the shoji have eyes’ (Kabe ni mimi ga aru, shoji ni me ga aru).

Fig.7. ‘Young Couple and peeking girl‘ (c.1760s) from the series ‘Senrikyu‘ by Suzuki Harunobu

The voyeurs actually represent us, the viewer, who, while looking, are secretly watching the lovers. In many cases, close inspection of a print, will reveal an eye peeking through the door. This enhances the viewer’s imagination to try to guess who it belongs

to, and what he or she is doing.

The mirror is also a popular motif and often used as a peeking device. Mirrors can provide another angle for observing couples and their intimate members. Sometimes the sexual act was hidden from the direct look of the beholder but was visible by its reflection in a mirror. The mirror’s position if often not related to what we see in it, but it will be the focus of attention of the image. This opens a window on to a meaningful aspect: either the beauty of the couple’s faces or to emphasize their sexual organs.

Rape

Rapists (Fig.8) are often depicted as Yakuza or brigands, discernible by their black clothes and handkerchiefs, or as highway bandits, sometimes stealing the clothes of a woman. Prints shows all sorts of men as perpetrators, who sometimes also get involved in a gang rape. Importantly. most rapists are portrayed as having physically repugnant peculiarities, such as an unusual amount of body hair, or unshaven or disfigured faces.

Rapists sometimes approach women while they are asleeep, hoping they will not wake up. From time to time a woman tries to defend herself, or another woman, by attacking the rapist. There are also some portrayals of women forcing themselves on a man (mostly a youth), sometimes even tying them up, though the accompanying text makes clear that such acts are committed only by desperate and undesirable women.

Fig.8. ‘Rape scene‘ (c.1896) from the series ‘Yakumo no chigiri ( Poetic Intercourse )‘ by Tomioka Eisen

Deities, Demons, Ghosts & Animals

Motivated by Confucian and Daoist beliefs, imported from China, the Japanese were taught that sex is important for both physical and mental health. From the Heian era, it seems most scrolls were owned by the aristocracy and temples. This is perhaps the reason why gods appear frequently, and not to mention the creators of the Japanese islands, Izanami and Izanagi.

In addition, there are The Seven Gods of Fortune (Shichi fukujin), who were frequently portrayed taking part in orgies. The same applies to Buddhist angels (tenshi/tenyo), who have intercourse with each other or with mortals. Another beloved figure was the demon Tengu, who is sometimes shown having sexual relations with a woman, usually using his long nose for her pleasure. Daruma, the founder of Buddhism was also a very popular subject (mostly in a humorous context).

Fig.9. ‘The nose of Daruma (Asahina and a young foreign boy)‘, c.1830. By Utagawa Kuniyoshi’

Demons (oni) were depicted having sex with, or raping, women or men. Raijin, the god of thunder, also appeared in scenes involving

rape. It was said that women should not bathe during thunderstorms, because the god might violate them.

There was a widespread popular belief in ghosts, and so they appear in many prints, including ghosts raping men or women, usually in dark places or cemeteries, as well as rokurokubi ghosts. They live like normal people during daytime, but at night can stretch their necks to an enormous length, and are known for their habit of disturbing humans and their love of drinking oil.

Although the majority of prints in this sub-genre show dark settings, such as a ghost emerging from a male organ, but there are also the humorous ghost images of the mythical character Minamoto no Yorimasa who is transposed from a painting into a physical body and making love to a female deity, or ghosts appearing in the shape of a variety of different animals.

Prints featuring animals are divided roughly in two categories namely the ones that are portrayed in fantasy scenes and those featured in realistic images. The animals depicted in the imaginative pictures include the rape of women in (or at) the sea (usually abolone divers) by collosal octopuses or kappa (water demons), or a half-octopus, half-human monster forcing himself on a fisherman’s wife.

Fig.10. ‘Fox Spirit‘ (c.1850) from the series ‘Shunshoku Tamazoroi (An Assortment of Pleasure in Spring)‘. Designed by Utagawa Kunisada

Foxes (kitsune) mutate themselves (see Fig.10.) into male or (more usually) female human form to trick people into having sex or to try to obtain something from them in return for sex. They were shown either as foxes dressed as humans or as humans with tails. In some toy prints (shikake-e), what appears to be a woman is revealed as a fox when a flap is lifted. Sometimes a priest performs rituals to prevent a fox deceiving a woman into having sex.

Animals portrayed in real settings are dogs, foxes, cats, monkeys, deer, camels, turtles and mice, who copulate with each other, or participate or watch the intimate human couples. Perhaps the purpose was to compare the two and convey the idea that humans are also animals, simply acting as nature intends.

Larger animals are also represented, including oxen looking on with interest while humans make love, or horses having erections while observing a couple in action. Sexual acts between humans and animals are also shown, but mainly in the form of parody. Usually one human (either man or woman) has sex with a single animal, typically a dog or a horse but also an exotic animal such as a camel.. ..

Fig.11. ‘Canine Hero Yatsufuta‘ (c.1837). Series: ‘Koi no yatsufuji (Eight Dog Heroes)’. Utagawa Kunisada

Most of such portrayals of sex with animals were intended as lighthearted and comical, sometimes very noticeably so, as when a horse dressed in a kimono is cleaning himself licking his penis after making love to a woman.

Amusing or not, it is difficult to believe that the majority of people looking at prints featuring ghosts, animals or monsters, would experience any lust or sexual arousal.

Homosexuality

Homosexuality has appeared in Japanese art from the Heian era (late 8th Century). It is rumoured that homosexuality was imported from China by the Buddhist priest Kukai (774-835). The most compelling aspect of known Edo-period portrayals of homosexual sex is the clear differentiation of the partners in terms of their ages. The partners’ respective ages determined their sexual roles. This was called ‘the way of youth’ (shudo or wakashudo). The receptive partner (wakashu), perpetually a pre-pubescent or pubescent boy or an adolescent male, could assume no role other than submission to anal penetration by the senior partner (nenja).

These young boys were often young male prostitutes called yaro, although they had many other names such as nanshoku (‘male colours’) or kagema (‘hidden room’). Their services could be hired in brothels that were called ‘houses of children’ (kodomo-ya).

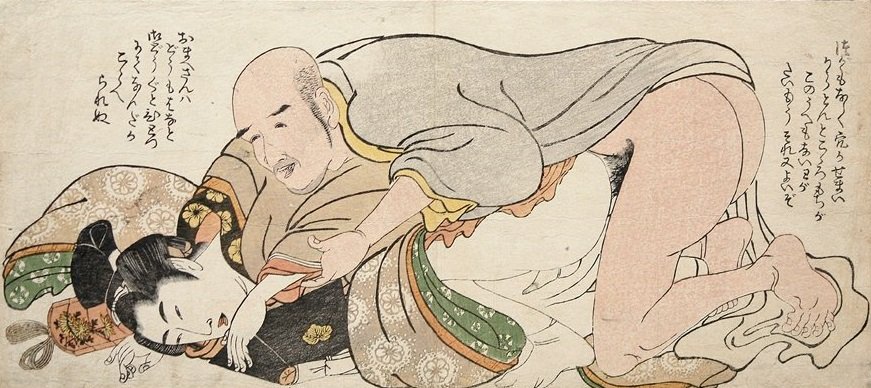

Fig.12. ‘Temple page and monk‘ (c.1803) From an untitled series published in the rare half-size oban format. Designed by Kitagawa Utamaro

Male homosexuality does not follow the present-day understanding of homosexuality. That is a sexual relationship in which both men are by nature attracted to each other. But what we usually see is that one party enjoys the act, while the other, usually a younger male, gives his body out of respect or duty (giri), or for money. The older male will never hire boys to penetrate him.

Sometimes images featuring homosexual activity were intended to express criticism on behavior of a different kind. For instance, when a samurai is shown forcing himself on a farmer, the clear implication is to criticize samurai exploitation of farmers and other lower classes. Often homoerotic scenes feature priests and Buddhist monks who make love to their male najimi (regular partner). A recurring theme within this sub-genre is that of the young male making love to a girl or woman while a senior partner penetrates him.

Westerners (Foreigners)

Since the first Portuguese ship arrived in 1543 the curiosity of the Japanese about these foreigners was intense. Although it was not until the 1630s when Dutch merchants were allowed to enter the mainland that they could observe them more closely. But it was not until the eighteenth century, though still in restricted areas only (Maruyama and Dejima), that the Japanese and a very few Europeans were allowed to intermingle.

The first scenes that were created of these barbaric Westerners were inspired on the relationships between Deijima factory men and Japanese women. This resulted in humorous erotic scenes and fanciful commentaries in the illustrated books and prints dating from the 1750s to the early nineteenth by artists such as Tsukioka Settei, Shiba Kokan, Hosoda Esihi, Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai.

Fig.13. ‘Foreigner with a Japanese woman (c.1800)’ from an unknown series by Kitagawa Utamaro

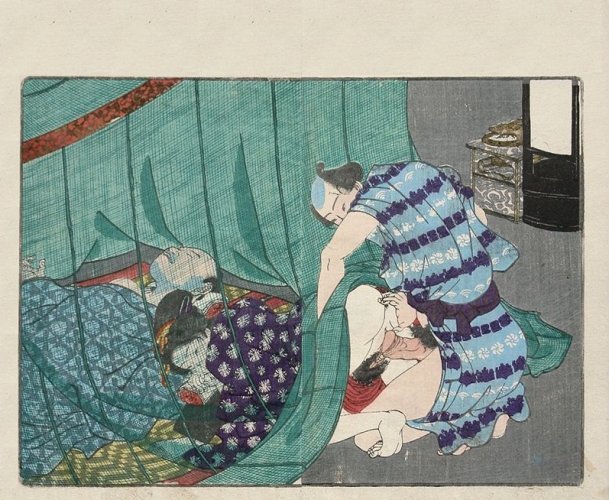

Mosquito netting

The use of mosquito-netting had not only a compositional purpose (conjuring up a separate world) but it was also a way for the artist to convey the summer season to the image. The rendering of the mosquito net is a stunning example of nishiki-e printing techniques, in which vertical and horizontal green lines were superimposed in two printing stages to represent the weave of the hempen net, over which a further screen of faint green was applied. The seafloor-like atmosphere of the interior of the mosquito net is thus superbly conveyed. Carving the weave of the mosquito net presented such a challenge that most prints on this theme depict the lovers outside the raised net.

Fig.14. Series: ‘Shiki no sugatami (Viewing Forms in the Four Seasons)‘, c.1842. Title: ‘Lovers and Sleeping Husband‘ By Utagawa Kunisada

What are the specific aestethics of Shunga?

To fully appreciate the art, it is important to remember that they were designed from a male perspective and consequently that the depictions of women were intended for a male audience.

The prints have always held a special position because their erotic subject-matter requires the artist to convey the complexities of sexual intimacy. They are a field of ukiyo-e rich in research potential, as no other genre provides the same insight into the abilities of an individual artist, or in the words of Jack Hillier: ‘Shunga often elicited works of art’.

The ratio between the imagery derived from the Yoshiwara and shunga rooted in scenes from daily life is hard to measure. This probably has something to do that the setting shifted over time. Everyday scenes may have predominated the period from 1765 to 1780, that is, sometime during the careers of Harunobu and Koryusai. Nevertheless, in numerous nineteenth-century book illustrations by Eisen, Kunisada and Kuniyoshi, the settings were frequently brothels and houses of assignation.

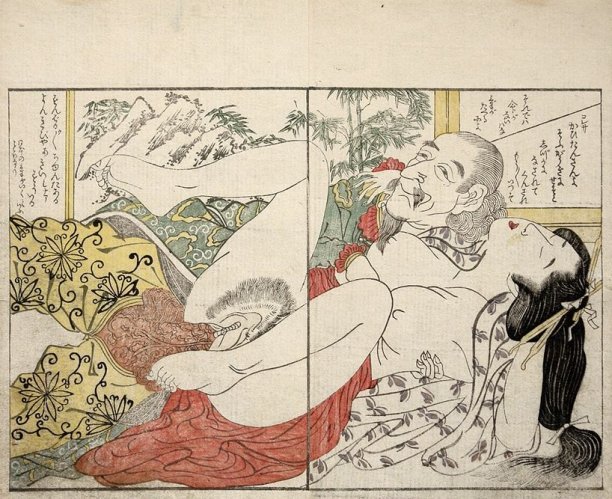

The exaggerates genitalia

It was Koryusai in the late 1770s who re-introduced the ōban format, and who also set the trend of exaggerating the portrayed genitalia. This greater emphasis on male and female genitalia had an aestethic point of departure. This way, the enlarged genitals would dominate the composition and immediately drew the viewer’s attention.

Fig.15. ‘Aristocratic couple‘ (c.1890s) from an untitled series attributed to Tomioka Eisen

Dutch ukiyo-e expert Uhlenbeck says: “The strong lines used to delineate genitalia create a dynamism that would otherwise be absent” and art historian Timon Screech has suggested that anatomical/gender differentiation is lacking. Rather, clothes distinguish men from women and this is why complete nudity is relatively rare. Furthermore, the enlarged sexual organs provide the ultimate method to distinguish men from women. The lack of gender-specific anatomy in prints compels the artist to focus on genitalia and clothing.

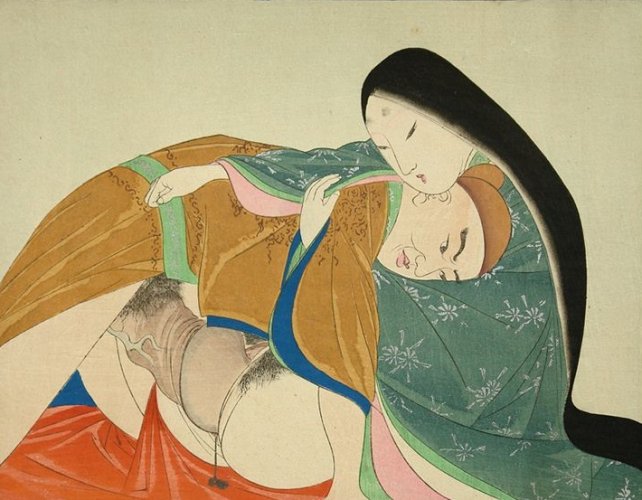

Textiles

Japanese art authority Tanaka Yuko makes the further observation that the prints are as a 'kingdom of cloth’. During the first two decades of the nineteenth century the artists Eizan and Eisen excelled in a style in which sexual activity is almost totally overshadowed by mounds of cloth. The gorgeous kimono patterns and the sumptuous fabrics indicate an opulence not encountered in shunga before this time.

Tanaka points out that perhaps this accent on fabrics had to do with links between ukiyo-e printmakers, drapers and textile designers. It would be interesting to know if drapery houses also sponsored shunga prints. Textiles thus set the ‘erotic’ stage and accentuate the compositional focal point – male and female genitalia.

Collecting tips

During the Edo period alone, around 3,000 books were created, plus a vast number of paintings, prints of various sizes (usually in sets of twelve), and more. It is almost impossible to collect everything, both because of the quantity and because of the rareness of items and their increasing prices. Therefore, my first advice to the collector is to concentrate on a specific niche close to his/her heart: a specific artist, a specific period of time or a specific subject.

Due to age and the fragility of the washi paper (handmade from natural fibres) on which works were printed, many suffer from the ravages of time and mistreatment, with damage such as burns, missing ages, worm holes, water stains, and colour bleeding due to moisture and humidity. Many have torn or worn lower corners as a result of excessive age turning. Some have been mounted on various later backings, filled-in with colours, or written over by successive owners.

The best method of storing your prints is to keep them between sheets of washi paper in hard-cover albums. If you would like to display them, place them on washi paper before framing, to avoid acidity, and keep them away from intense light, especially sunlight, which will cause the colors to fade.

Prices have risen consistently in the last few years and, given the gradual increase in freedom relating to the subject in Japan, will probably continue to increase. By taking good care of your collection, you will be enhancing its value and, more importantly, you will be helping preserve an important part of the art and history of Japan and the world.

We hope you enjoyed the article and wish you lots of fun learning about and collecting this art…!

Sources: ‘Japanese Erotic Fantasies’ by C. Uhlenbeck, ”Shunga, the Art of Love in Japan by Tom and Mary Evans, ‘Japanese Erotic Art, the Hidden World of Shunga‘ by Ofer Shagan, ‘Poem of the Pillow and Other Stories‘ by Gian Carlo Calza, ‘Japanese Erotic Fantasies, Shunga by Harunobu and Koryusai‘by Inge Klompmakers, ‘Shunga, Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art‘ by Timothy Clark, C. Andrew Gerstle and more, ‘Shunga, Stages of Desire‘ by Honolulu Museum of Art, ‘The Complete Ukiyo-e Shunga‘ (Vol. 2,4,5,7,12,14,15,16 and 18) by Hayashi Yoshikazu and Richard Lane.

Unveiling Your Passion: Erotic Aesthetics Redefined

Erotic Aesthetics Redefined

Digital magazine for Bold art lovers