Power, Eroticism and Creative Violence: The Art of Otto Muehl and the Legacy of Actionism

The theme of Abject Art, despite its surface-level repulsiveness, existed in my mind as something fascinatingly unspoken—not merely as a byproduct of controversy, nor as the echo of a childish need to provoke, but as something profoundly human, and yet rejected by traditional humanistic discourse.

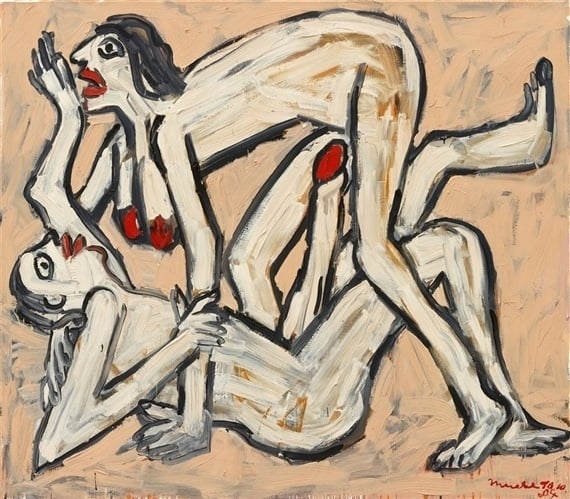

Fig.1

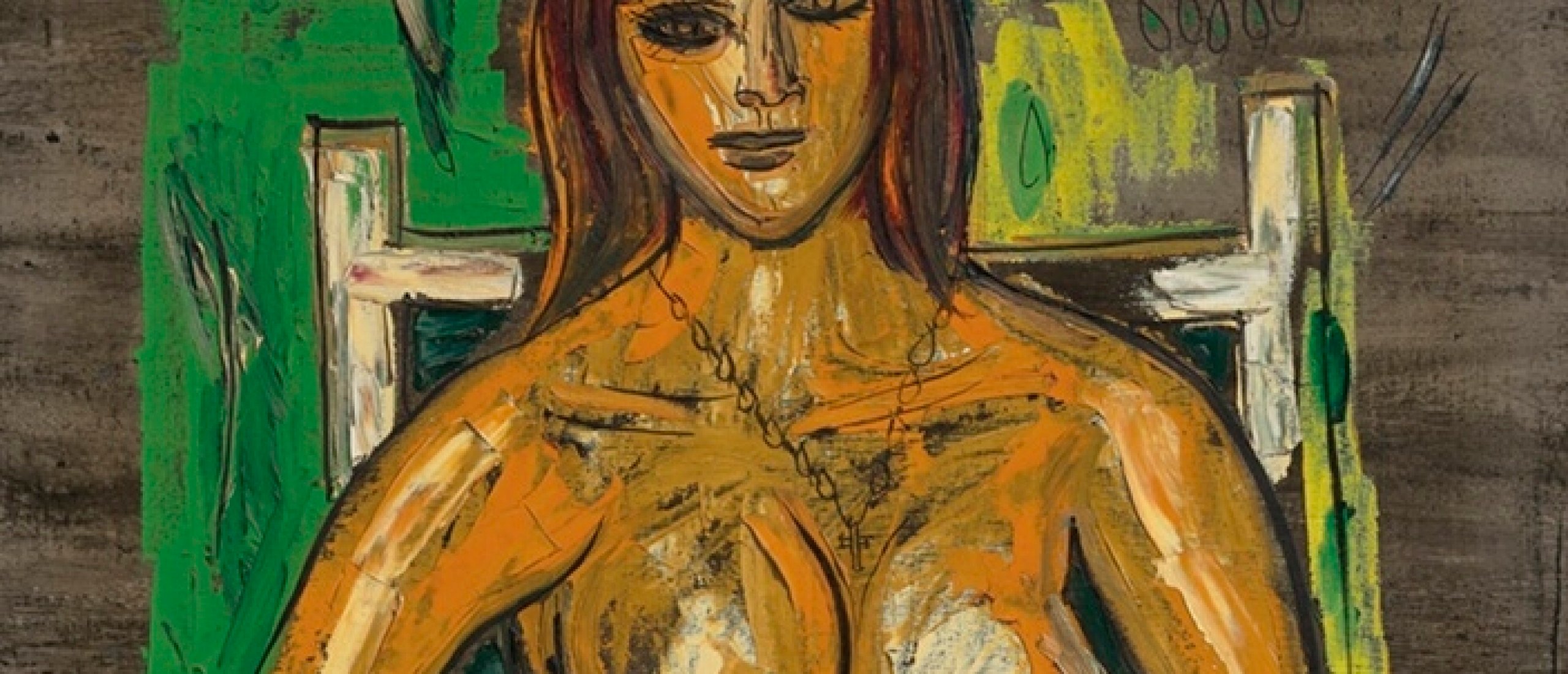

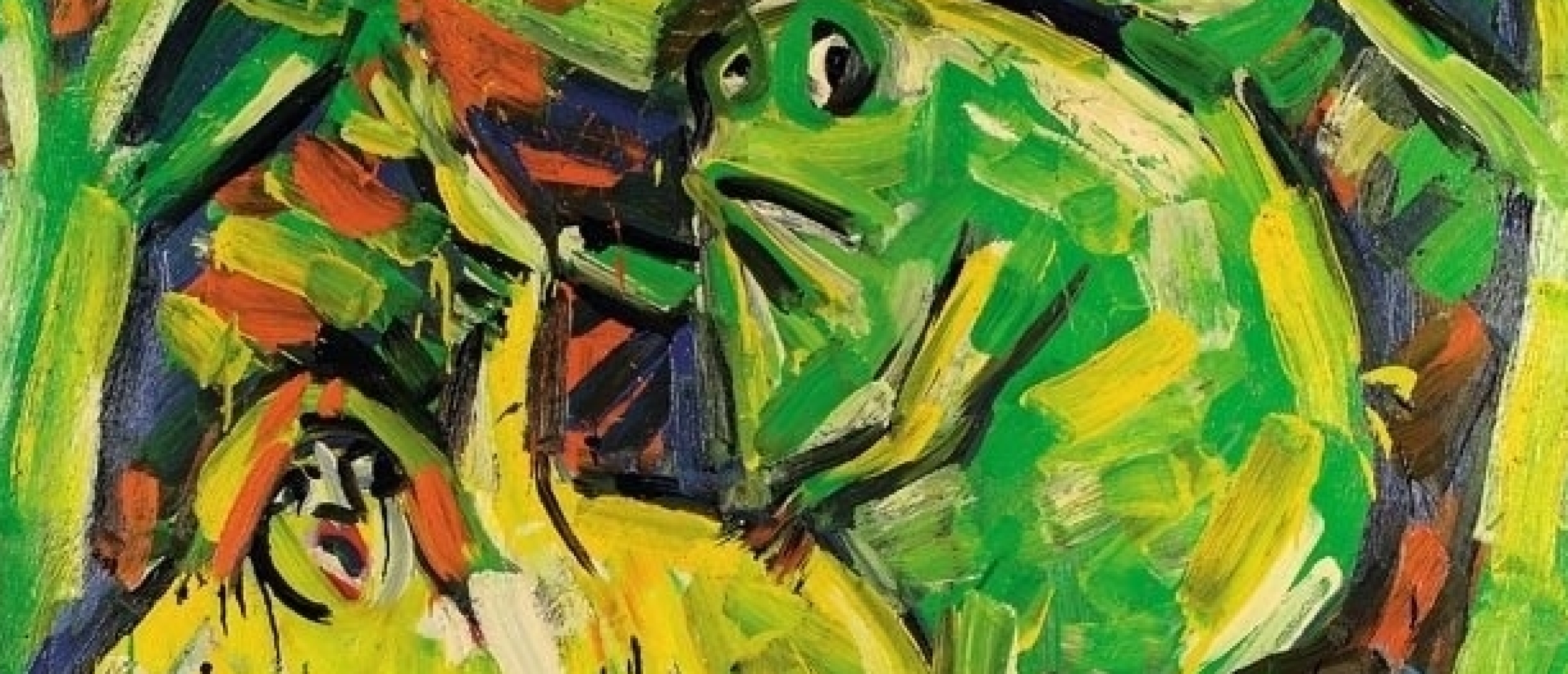

Fig.2

Powers of Horror

Its appeal lies not in the disgust, revulsion, or outrage it provokes in most viewers, but rather in the way those reactions reveal something fundamental: the socially constructed boundary between what is accepted and what is cast out. The central question I kept returning to while reading Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection concerned this very boundary—where exactly is it drawn, who enforces it, and on what basis does a chosen medium or subject matter become “acceptable” or “unacceptable”?

Outright Disgraceful

During my university years, while studying modern and contemporary art, nothing shifted my understanding of what constitutes a work of art more profoundly than learning about the Vienna Actionists. Lectures on a movement hatched from the rotting entrails of postwar Europe completely upended my understanding of how artistic expression operates—of the structures that govern societal permission regarding what should be shown, what is better left unsaid, and what kind of showing is simply wrong, immoral, or even outright disgraceful.

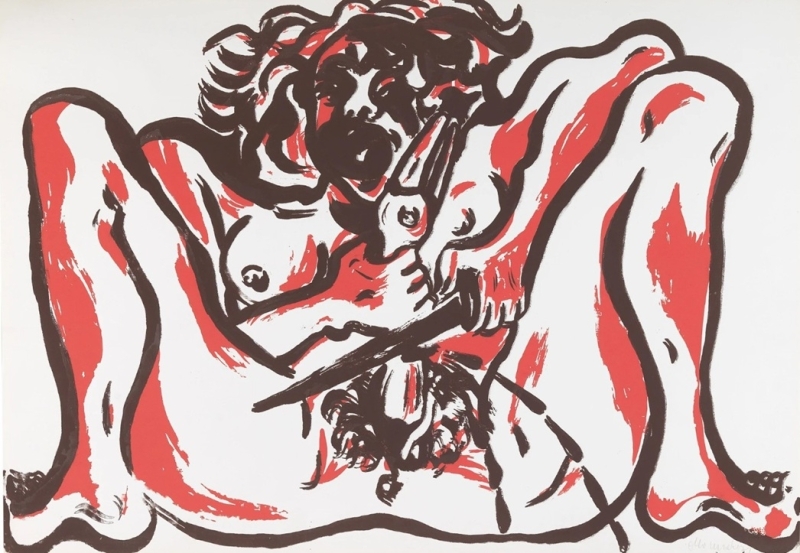

Fig.3

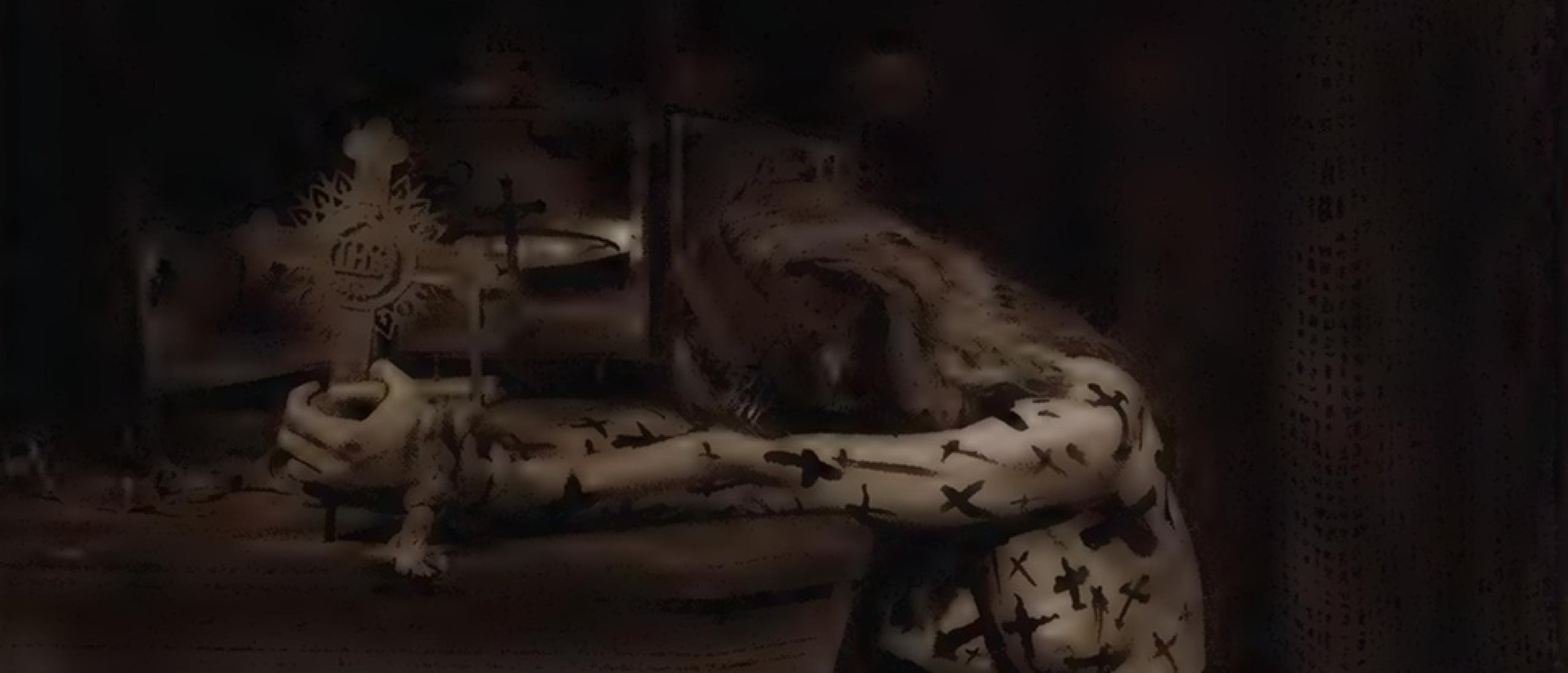

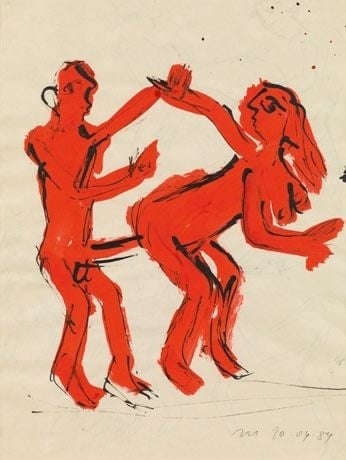

Fig.4 The Frog Prince, 1984

Neurotic Spasm

Actionism emerged in the mid-20th century as one of the many malignant offshoots of its diseased era. One of the movement’s founding figures, Otto Muehl, was arrested and spent two months in jail following his performance Art and Revolution at the University of Vienna in 1968. The event caused considerable uproar—understandably so. Many art critics argue that with this performative outburst, the Actionists put a final period at the end of the long, unnecessarily exuberant sentence called the history of art. Everything that followed, they say, is but a neurotic spasm—a pathetic twitch of a dead body pretending to still be alive.

Violence and Savagery

Otto Muehl, however, held a very different view. He continued his artistic practice, turning toward painting and screen printing. Among the results were cycles such as 12 Aktions and Persönlichkeiten (Personalities), which—like earlier Actionist work—provoked controversy through their brutality and grotesque depictions of violence and savagery. Yet the absence of that electrifying, eerily familiar madness in Muehl’s later works only reinforces the notion that Art and Revolution marked the definitive end of fine art—a conclusion that is, at once, both unsettling and strangely reassuring.

Fig.5 Untitled, 1996 (artsy.net)

Fig.6

Fig.7 Materialaktion no.19 (Bodybuilding), 1965

In the extended Premium edition of the article more on the aesthetics of Muehl's 12 Aktions and Persönlichkeiten (Personalities), his establishment of the radical left-wing commune—the Aktions-Analytische Organisation (AAO), the documentary on this commune, Meine keine Familie (My Fathers, My Mother and Me), many additional artworks and MUCH more...!

Click HERE for the bloody bacchanalias and dying Gods in The Orgies Mysteries Theater of Hermann Nitsch

What do you think about Muehl's work? Leave your reaction in the comment box below...!!