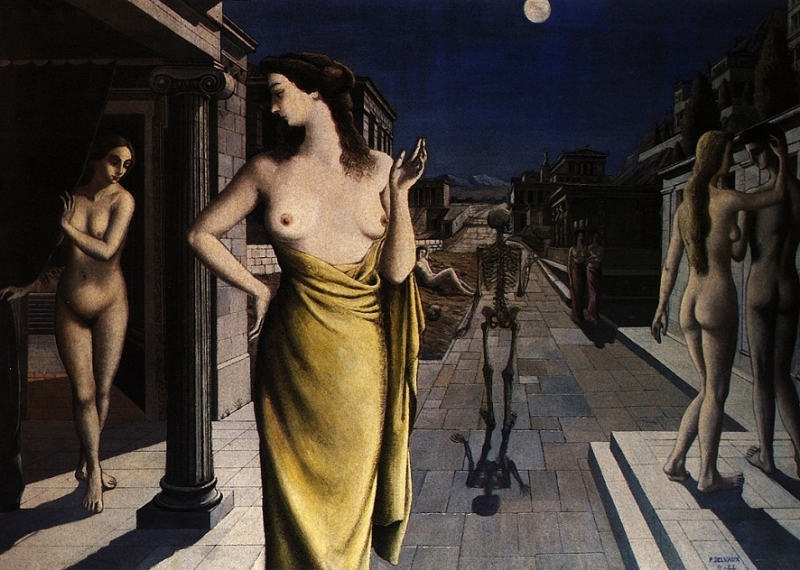

Paul Delvaux (1897-1994) was an independent long-liver who seemed to stand aside the surrealist movement with its' scandals, manifests, and political issues. Yet he was apparently influenced by some of the prominent figures of surrealism, like de Chirico with architectural geometry of the paintings and probably his compatriot Magritte with buttoned-up males and naked females. The image of beautiful women, who, with a mystery in their large eyes, wander in a space resembling Robbe-Grillet's labyrinth, makes the art of Paul Delvaux quite recognizable.

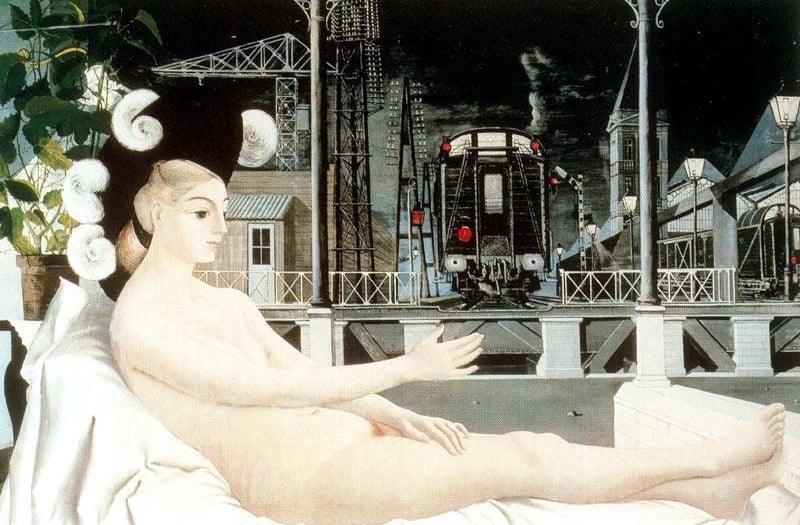

Fig. 1. The Village of the Sirens, 1942 (wikiart.org)

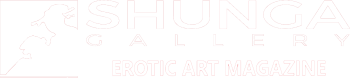

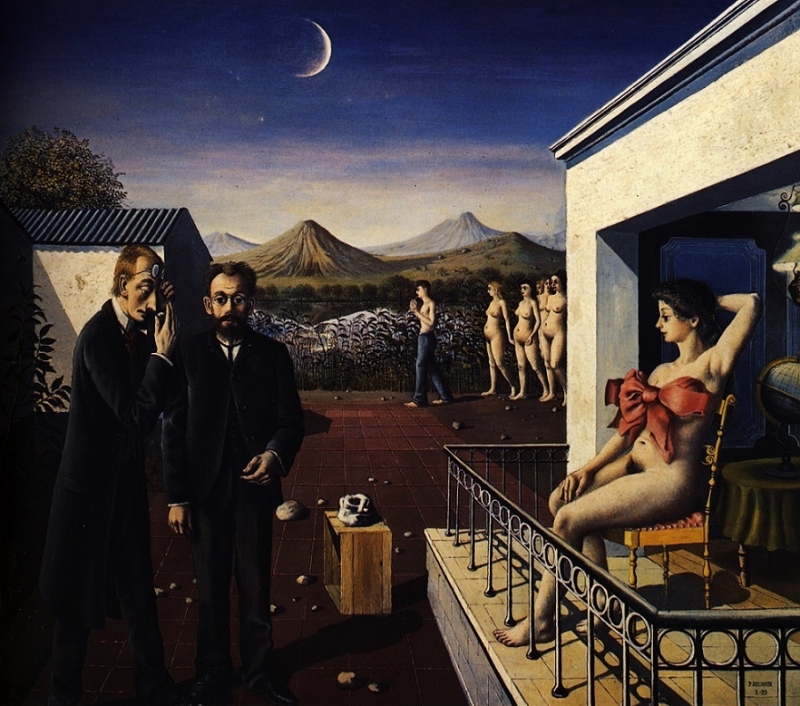

Fig. 2. A Siren In Full Moonlight (wikiart.org)

Fig. 2. A Siren In Full Moonlight (wikiart.org)

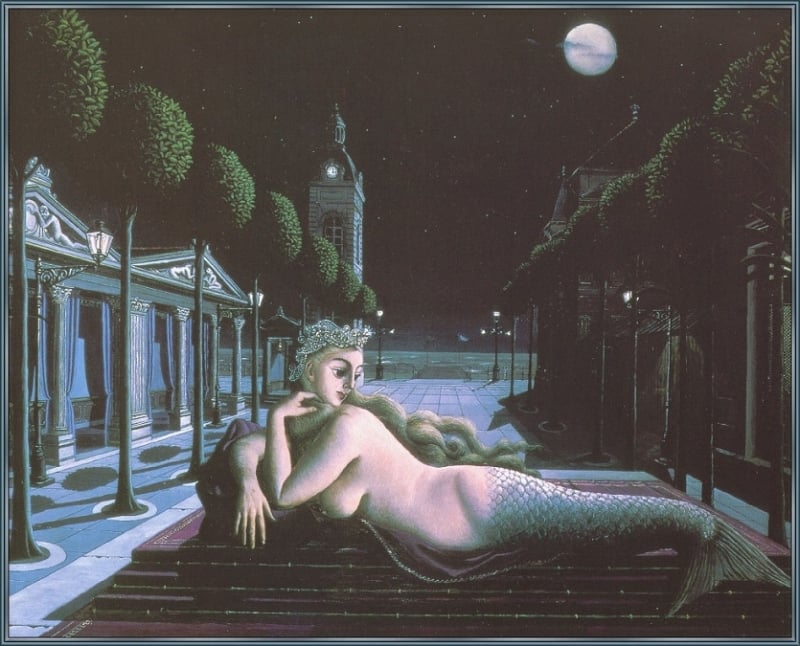

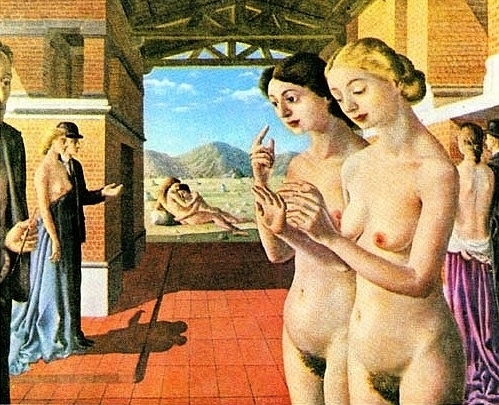

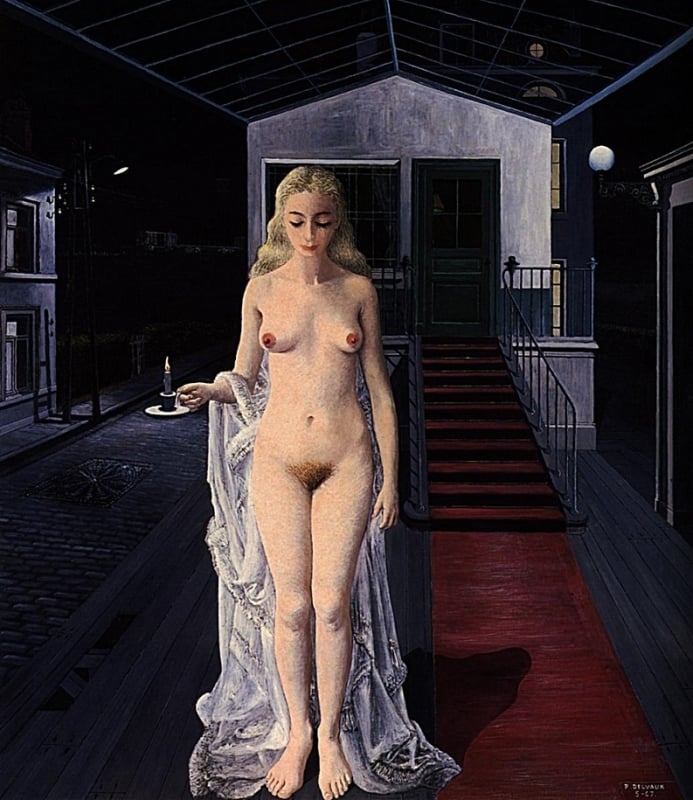

Fig. 3. Nudes, 1946 (wikiart.org)

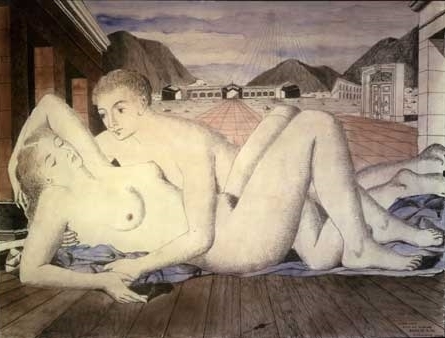

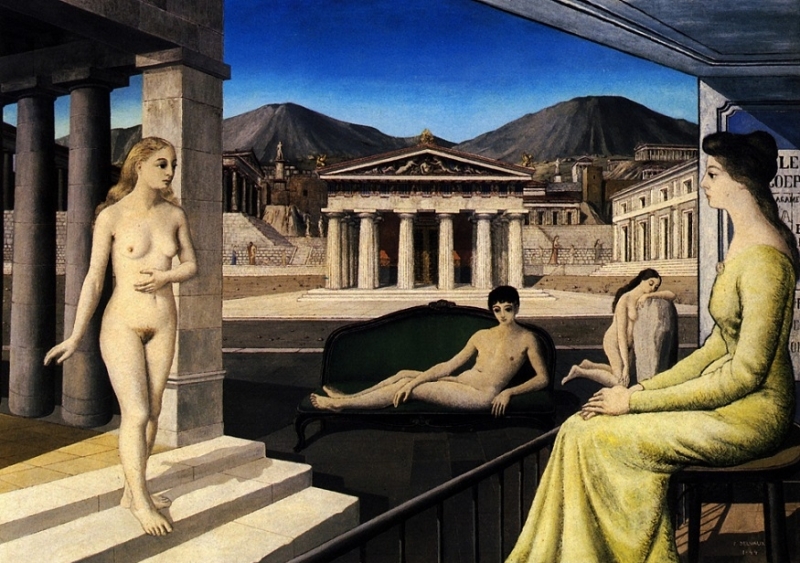

Fig. 4. Echo, 1943 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 4. Echo, 1943 (wikiart.org)

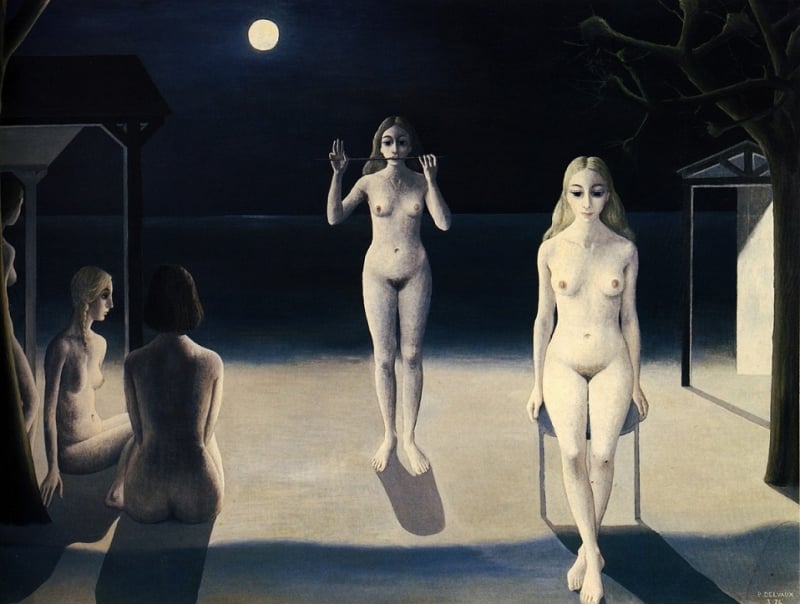

Fig. 5. Night Sea, 1976 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 5. Night Sea, 1976 (wikiart.org)

Mothers And Sons

Delvaux was born in Antheit, Liège (Belgium), and received a classical education: he studied Greek and Latin, read Homer, and took music lessons. Allegedly, the future artist was raised by a possessive mother, which caused his fear of the feminine world. This inner psychological motif of his paintings is another feature a bit similar to that of Magritte, who was affected by his mother's suicide. Both painters often oppose men to women, depicting the former as fully dressed and the latter as nude. In their works, femininity is represented as something vulnerable yet dangerous. Delvaux gives his women an appearance of a femme fragile to emphasize their unsafe nature. As their careers started almost simultaneously, one artist could hardly be inspired by another. Still, their aesthetics seem much alike.

Fig. 6. Ecce Hono, 1949 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 6. Ecce Hono, 1949 (wikiart.org)

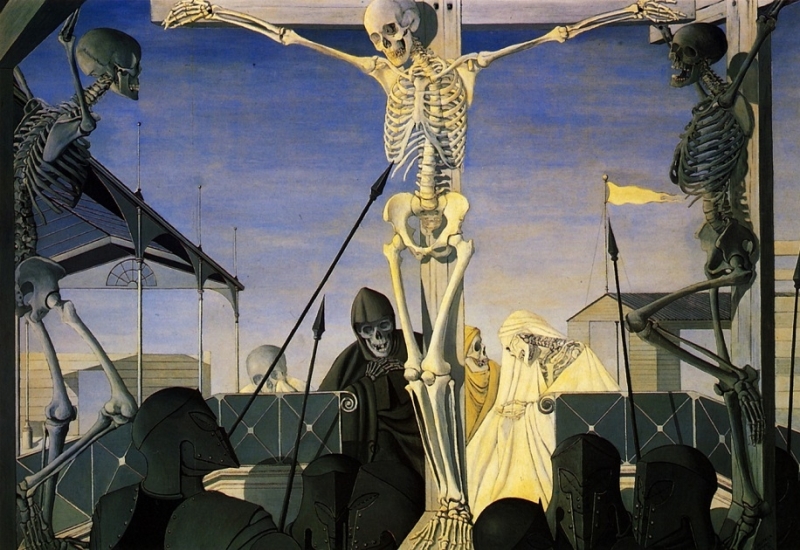

Fig. 7. Crucifixion, 1952 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 7. Crucifixion, 1952 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 8. The Deposition, 1951 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 8. The Deposition, 1951 (wikiart.org)

Crucified Skeletons

Delvaux studied architecture at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels because his parents didn't want him to be an artist. It was his teachers and friends who encouraged Delvaux to become a painter. The artist attended painting classes by Constant Montald and Jean Delville. His friend, painter Émile Salkin, also taught him to draw and instilled in the artist enthusiasm for anatomy by bringing him to the Museum of Natural History in Brussels. Skeletons would be a leitmotif of Delvaux's works. Passions of Christ with every human figure depicted as a skeleton remind us both of x-rays of Wim Delvoye and medieval danse macabre.

Fig. 9. Hands, 1941 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 10. Lunar City, 1944 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 11. Night Train, 1947 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 11. Night Train, 1947 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 12. In Praise of Melancholy, 1948 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 12. In Praise of Melancholy, 1948 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 13. Popular Cry, 1948 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 13. Popular Cry, 1948 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 14. Pygmallion, 1939 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 15. Sirens, 1979 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 16. Nymphs Bathing, 1938 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 16. Nymphs Bathing, 1938 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 17. Salut, 1938 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 17. Salut, 1938 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 18. Silent Night, 1962 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 18. Silent Night, 1962 (wikiart.org)

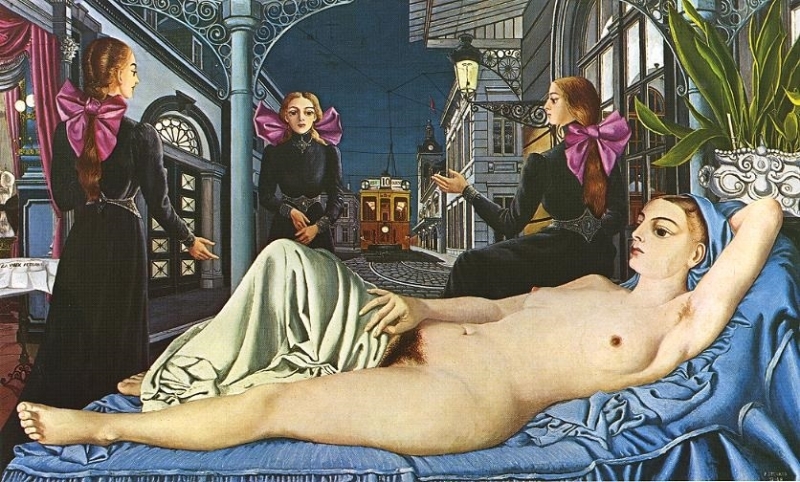

Fig. 19. The Girls From The Provinces, 1962 (wikiart.org)

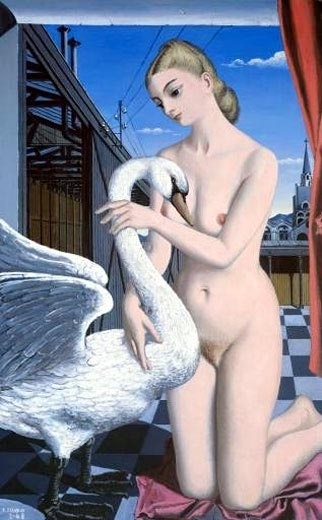

Fig. 20. Leda (wikiart.org)

Fig. 21. Iron Age, 1951 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 21. Iron Age, 1951 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 22. Phases of the Moon, 1939 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 22. Phases of the Moon, 1939 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 23. Phases of the Moon II, 1941 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 24. Chrysis, 1967 (wikiart.org)

Man A Machine

Besides the skeletons, another source of inspiration for Delvaux was the mechanical Venus of Dr. Spitzner exposed at the Midi Fair in 1932. It was a wax figure dressed in a nightgown. It actually "breathed" as its chest rose and fell. This showpiece was exhibited in a doorway framed by red velvet curtains. The sight captivated Delvaux and influenced the image of the woman in his pictures and especially a "serene" facial expression. Let's mention that the representation of a human being as a mechanism was promoted in the time of the Enlightenment, for example, in the famous treatise Man a Machine by De la Mettrie. Although Delvaux never depicted the human body in the section, the human-machine concept comes to mind as we look at numerous train stations and the complicated architecture of the urban setting in his paintings. The beginning of the XXth century, as well as the 17th-18th centuries, was the time of immense interest in various engineering inventions.

Fig. 25. The Awakening Of The Forest, 1939 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 25. The Awakening Of The Forest, 1939 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 26. The Concert, 1940 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 26. The Concert, 1940 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 27. Birth of Venus, 1947 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 27. Birth of Venus, 1947 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 28. The Congress, 1941 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 28. The Congress, 1941 (wikiart.org)

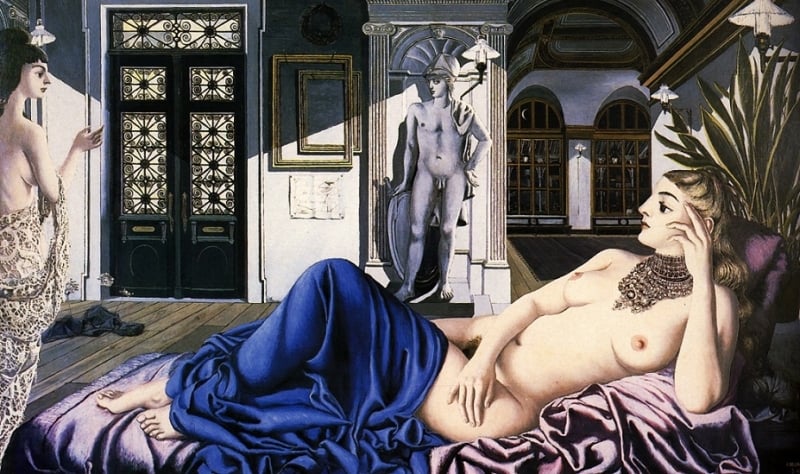

Fig. 29. The Canape Vert, 1944 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 29. The Canape Vert, 1944 (wikiart.org)

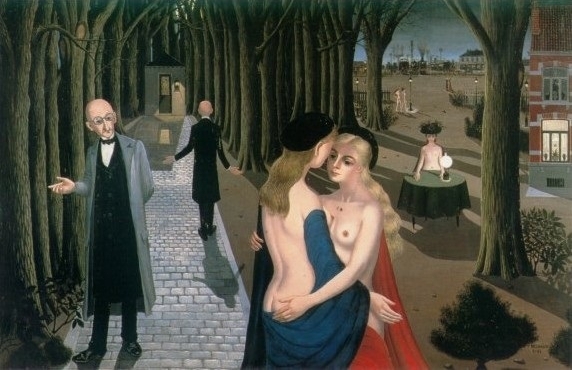

Fig. 30. A Visit, 1939 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 30. A Visit, 1939 (wikiart.org)

In Premium more secrets about Delvaux's nude nymphs will be revealed, larded with 20 additional enticing examples.

Sources: Wikipedia.org; wikiart.org; Francky Knapp. The Curious Case of Miss Mechanical Venus (messynessychic.com)