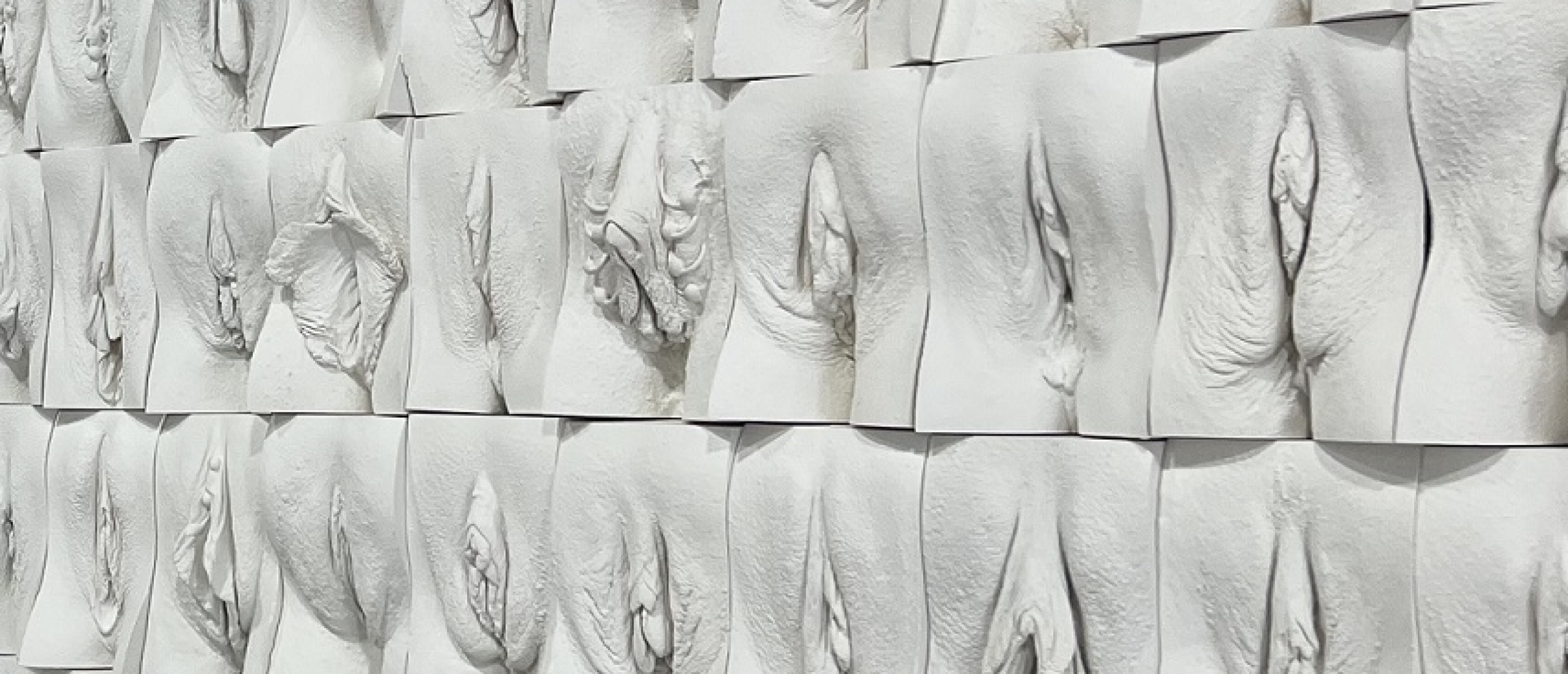

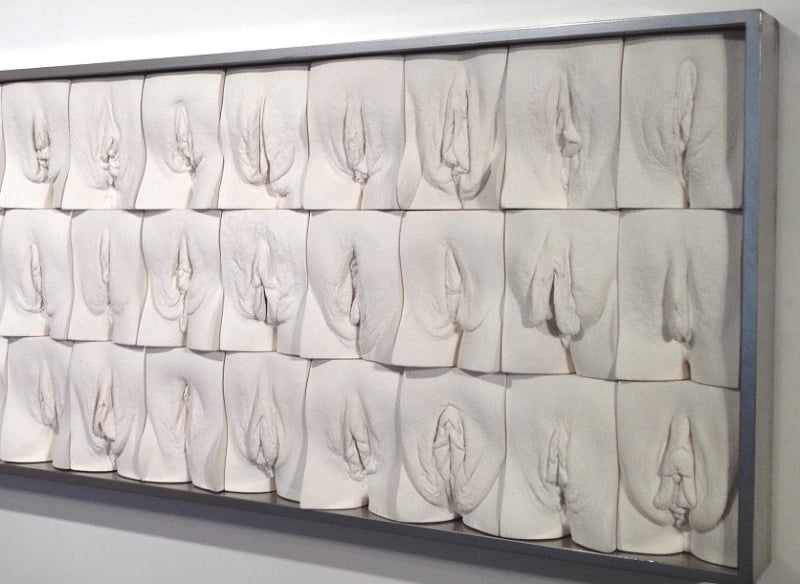

About a year ago, I was approached by the British artist Jamie McCartney (October 9, 1975) who told me about his iconic work The Great Wall of Vulva and that it is the centrepiece of the renowned erotic museum WEAM in Miami (which houses the largest collection of erotic art in America) for the next three years. The work is now in its third international museum exhibition and got a lot of press in Japan, where it was even banned, having been branded obscene by the Tokyo police in 2013.

Shunga

The artist came across our site as his art has a strong connection to shunga and he is also an avid shunga collector (more about this later in our conversation), and asked me if we would be interested in featuring his erotic work and the story of its creation to the readers of Shunga Gallery.

"Genital" Works

We agreed to do an interview but due to a major move of the artist's studios and house, involving many months of packing and building, the artist could hardly make time to respond to our questions in detail. Now that the dust has settled a bit, McCartney has taken his time and elaborates on, among other things, the aesthetics and themes in his work, influences of shunga and other artists on his art, the ideas about his "genital" works, and much more.

Fig.1. Jamie McCartney

Fig.1. Jamie McCartney

1) What can you tell us about your background (education, family, cultural environment?...etc. )

I grew up in central London and attended private schools but I never fitted into that environment. I was too rebellious and unconventional. My Dad was an engineer and my Mum is an artist. When she left my Dad she lived with Tony, a German film-maker who was my kind of crazy. He loved artistry in all its forms and he was the liberator of my creative expression, beyond the confines of a stuffy education system.

Fig.2. 3 x 3

Fig.2. 3 x 3

2) At what age did you realise you wanted to be an artist?

From a young age my Mum and Tony took me to all the museums and galleries and in those places I found myself. By the time I was ten years old, making art was what I was always going to do. Creating something from nothing, is a magical thing. Making art maintains my childhood wonder. It really is magic for adults.

Fig.3. 15 minutes

Fig.3. 15 minutes

3) Is there an overarching theme within your art? If so, how would you describe it?

My current fine artwork is always about the corporal and psychological experiences of humanity. It often tackles notions of beauty and sexuality and sometimes of inhumanity and depravity as a mirror to show the ugly sides of our species. I use whimsy and humour to invite you to see the world through my lens and then often unsettle you once I have drawn you in. That is how I bring socio-political purpose to the work. When you have a radical idea you find yourself often preaching to the converted. Reaching those who don't think your way already is the ultimate challenge.

Using the body as inspiration I work with both traditional and novel materials and processes, obsessively exploring the human condition. Some of my work is absolutely novel and has never been done before in the history of art. It is an incredible feeling to be a genuine pioneer. My tutors at art school also showed me how to use art as a tool for societal change. They were both Vietnam War veterans and one was a Native American. Their work was beautiful but it was also protest art. They inspired me to make work that wasn’t just pretty pictures.

Fig.4. 4 Women - bronze

Fig.4. 4 Women - bronze

I think of a lot of my work as art activism and a stand against body fascism, authority and dishonestly. I call it weaponised creativity. I try to be totally authentic and in so doing encourage it in my audience. I think humans are often so scared of judgement that we hide our true selves. Having the courage to expose our bodies and thoughts to public scrutiny is incredibly liberating. Ask my models! Overcoming that fear is the key to freedom. That is why censorship, such as that seen on social media, is such a scourge. It is fascist, reductive and dishonest, steeped in hypocrisy and fear. It stigmatises, misinforms and drives a narrow, Christian Right narrative that is grotesquely anti-human. Everybody has a responsibility to rebel against the limiting of their experience by those that seek to control us. This is why artists and radical thinkers are often persecuted and artworks and books are banned. We represent a threat to authority. You can judge a society by its tolerance of freedom of expression.

Fig.5 20 Women

Fig.5 20 Women

Fig.5a Detail

Fig.5a Detail

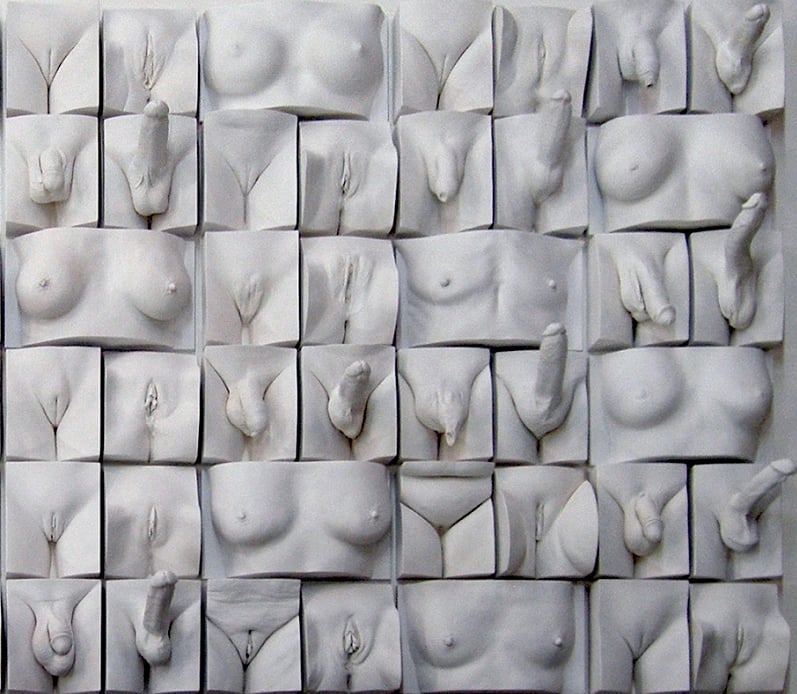

Fig.6 The Great Wall of Vulva at WEAM

Fig.6 The Great Wall of Vulva at WEAM

Fig.6a Detail

Fig.6a Detail

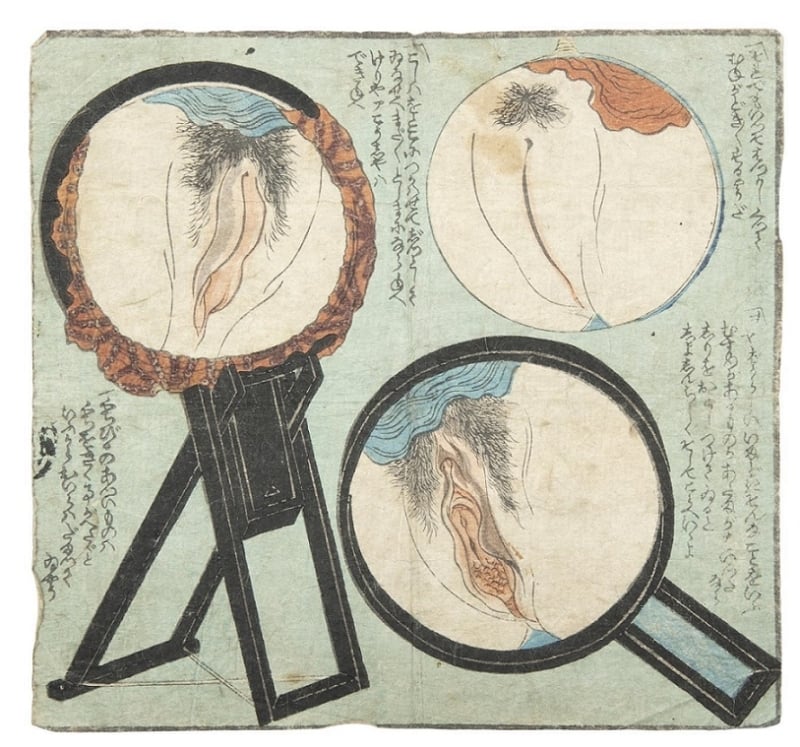

Fig.7. Opening plate from a small untitled folding shunga album depicting three different types of mirrors, imaging three different types of vulvas (c.1850) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Fig.7. Opening plate from a small untitled folding shunga album depicting three different types of mirrors, imaging three different types of vulvas (c.1850) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

4) You told me that this shunga print (see Fig.7.) by Kuniyoshi of mirrors reflecting various types of vulva inspired your 'The Great Wall of Vulva' piece. Why this specific piece?

Differences in human anatomy are generally ignored in sex education and in the simplified, medical diagrams in such materials. Through my own sexual experiences it was abundantly clear to me that there is no single version of a vulva or a penis, yet where was this described in Western anatomy books? There were no resources available to me to understand difference. Educational art was not representative of the science. The fusion of art and science has always interested me and it feels like a tragedy that they have become separate disciplines. That division impoverishes both. When you allow their marriage it is numinous.

Numinosity refers to the power of appealing to the higher emotions or to the aesthetic sense, surpassing comprehension or understanding. Science without consideration of numinosity can be dehumanising and ego driven. Science does not have all the answers. It is only ever our best guess at the time. Good scientists know this. Great scientists embrace it. They are artists.

When I first saw this shunga image I was struck by the sensitive and beautiful depictions of different vulvas. It mirrored my experience and fueled my fascination and desire. That felt very powerful and it was the first time I'd seen such imagery outside of the salacious provocation of pornography. This was different.

In the development of The Great Wall of Vulva, which was inspired by the women coming to be cast for a previous project (The Spice of Life - fig.8), this shunga image was very much in my mind. About a year ago I saw on original print of this image become available at auction and I knew I had to buy it. I have an extensive collection of shunga but this is definitely the piece I am happiest to own. Having it on display at home completes something for me.

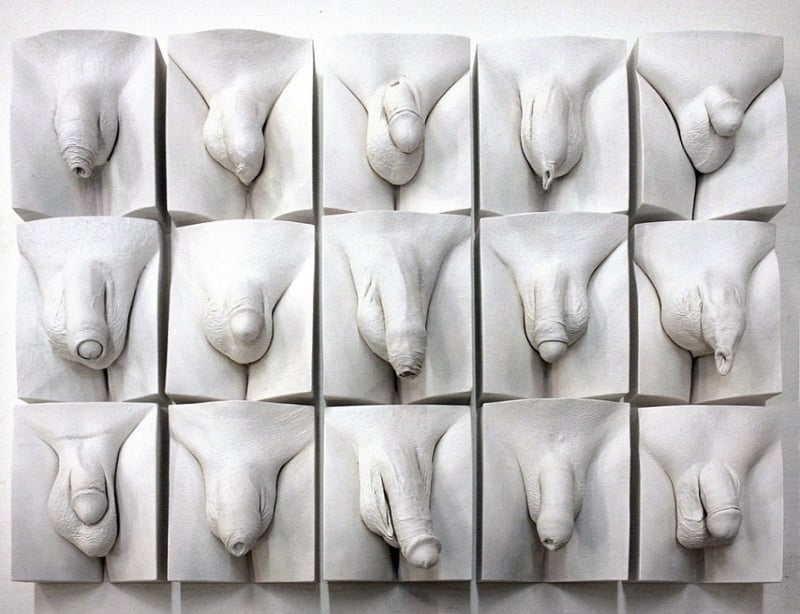

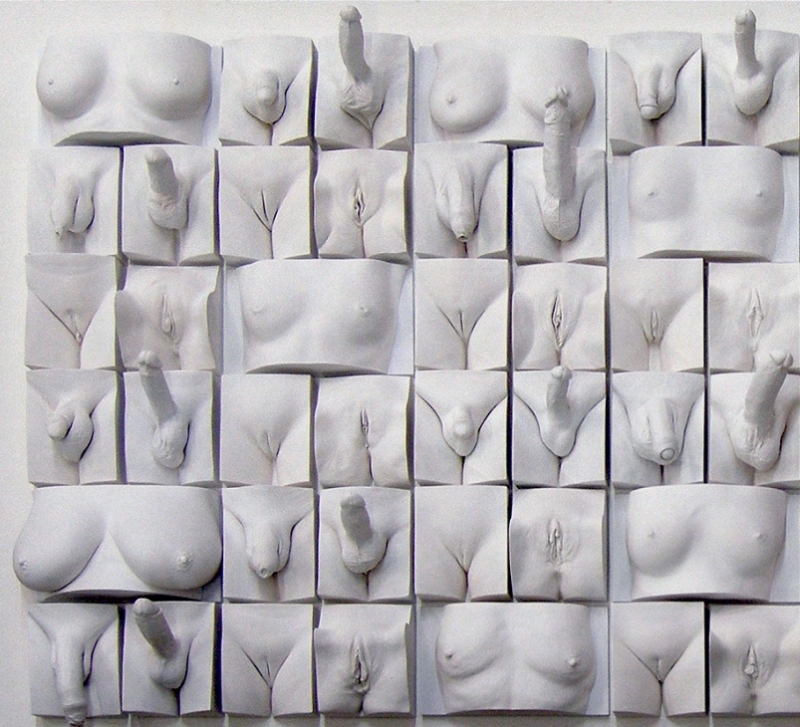

Fig.8 The Spice of Life

Fig.8 The Spice of Life

Fig.8a Detail

Fig.8a Detail

Fig.8b Detail

Fig.8b Detail

5) What do you think about the art of shunga?

I have been collecting shunga for many years and although my intellectual understanding of the work is limited, my aesthetic appreciation is profound. I was introduced to the world on shunga via my avid exploration of art history. Its intrigue for artists such as Picasso is well documented. In fact I would go so far as to say it influenced him greatly and some Picassos are a direct derivation of known shunga prints, as are his more erotic themes. The skill of the shunga artists, often unnamed, is incredible and their unashamed eroticism is very powerful.

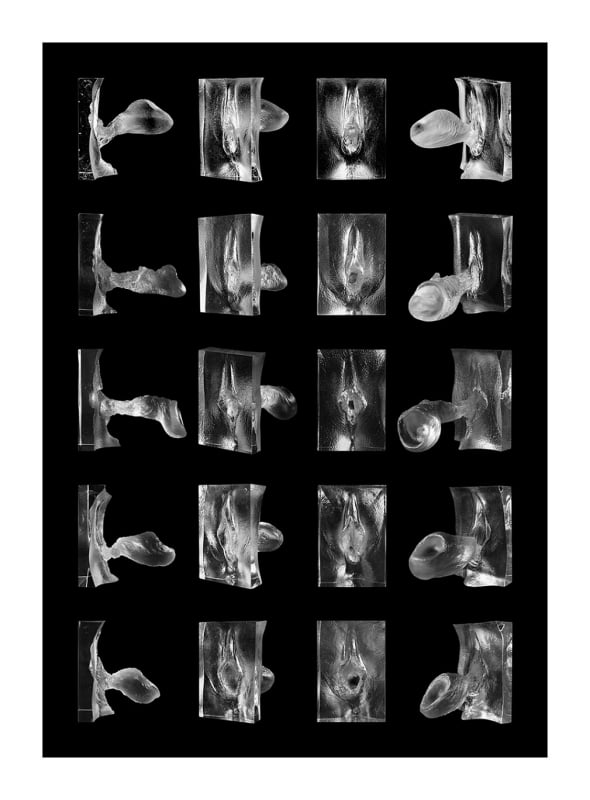

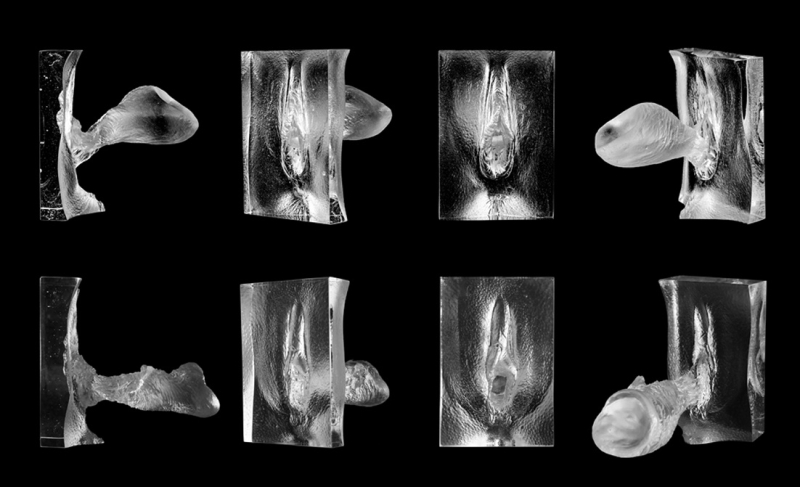

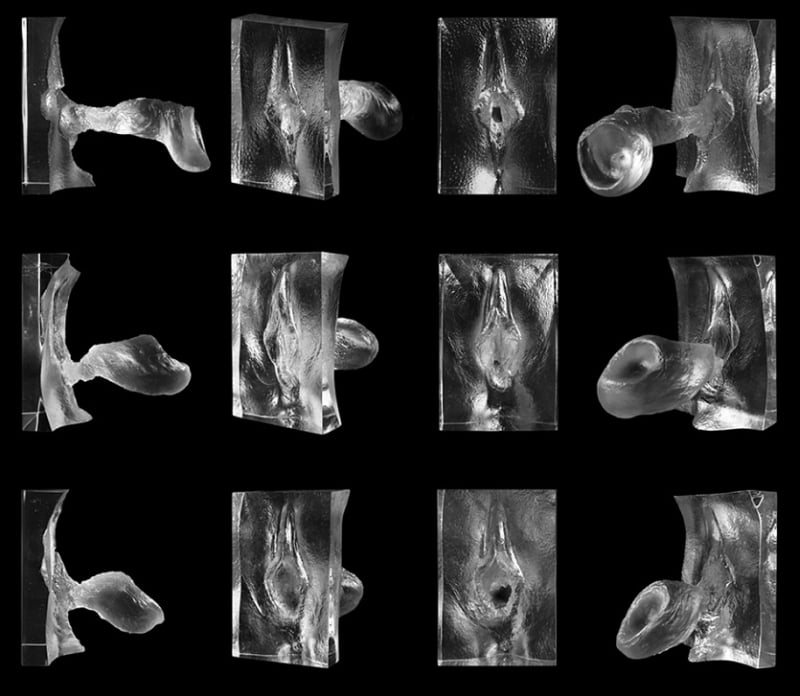

Fig.9 Photography series Internal Affairs

Fig.9 Photography series Internal Affairs

Fig.9a Detail

Fig.9a Detail

Fig.9b Detail

Fig.9b Detail

But the abstraction of the subjects’ bodies, through pose and brilliant structural devices, as seen in the best work, means there is action required by the viewer to read it. It is not the passive, conveyer belt of pornography but instead represents a genuine artistry that has been a significant influence on so much that has come since. There is also so much humour in shunga, laughing at the human condition and our obsessive sexual intrigue but in a completely sympathetic way. It genuinely accepts and presents what it is to be human, completely subverting the narrow Christian and post-Victorian attitudes of my own country. These strictures sought to suppress sexuality and distil it down to the most basic function of reproduction, which in my mind misses the entire point. The continuation of our species should be the happy result of our sexual intrigue, rather than it's sole purpose. I think shunga recognises and rejoices in this in a way that Western art only manages in a marginalised and underground way. Sadly, it is my understanding that Western morality was in part responsible for the marginalising of shunga in Japan during the last century.

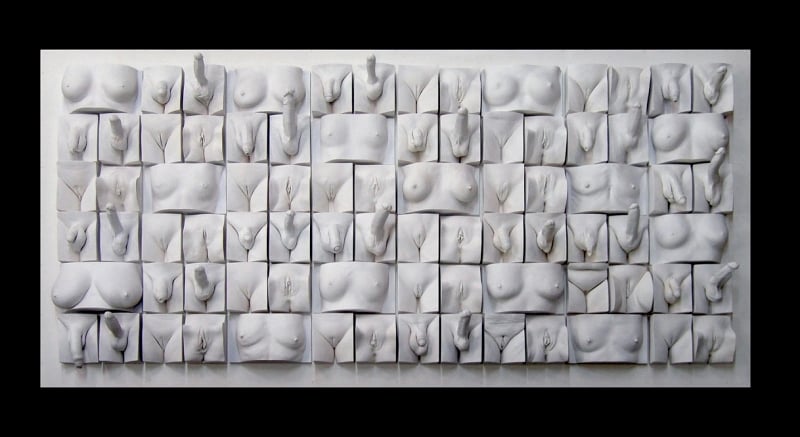

Fig.10 57 Women

Fig.10 57 Women

Fig.10a Detail

Fig.10a Detail

Fig.11 Dominate Subordinate (July 2018)

Fig.11 Dominate Subordinate (July 2018)

Click HERE for the follow-up to the interview

More on Jamie McCartney's work can be found on the artist's site!

Source: the images were provided by Jamie McCartney

Let us know your thoughts about the interview in the comment box below..!!