Editor’s Note: Beauty may lie in the eye of the beholder, but eroticism? That’s a private screening in the mind’s own secret cine-theatre where each of us carries a hidden visual compass decoding those fleeting signals of desire.

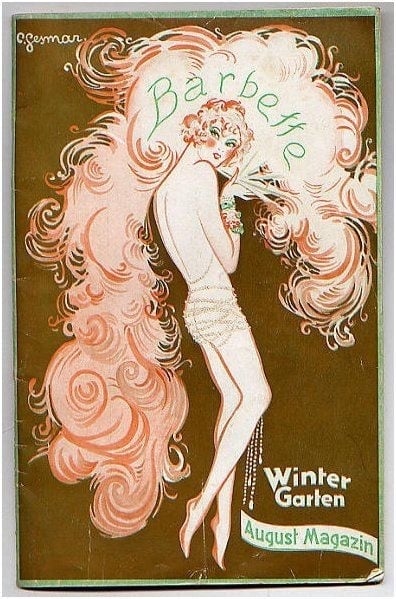

Eros/Eroticon is my ongoing love letter to Eros and Psyche, forever passionately embraced: a subject as ancient as Isis’ temples and as fresh as your last browser tab.

Eros is a paradox. It refuses to be neatly classified, yet it demands attention. It can be poetic or pornographic, delicate or obscene, refined or raw. It lives in a marble torso, in Michelangelo’s sublime declarations of male love, in the illicit sketchbooks passed between lovers, in Warhol’s Factory queens strutting downtown. This chapter: the men who loved men, their punishments and pleasures, their beauty and shadows.

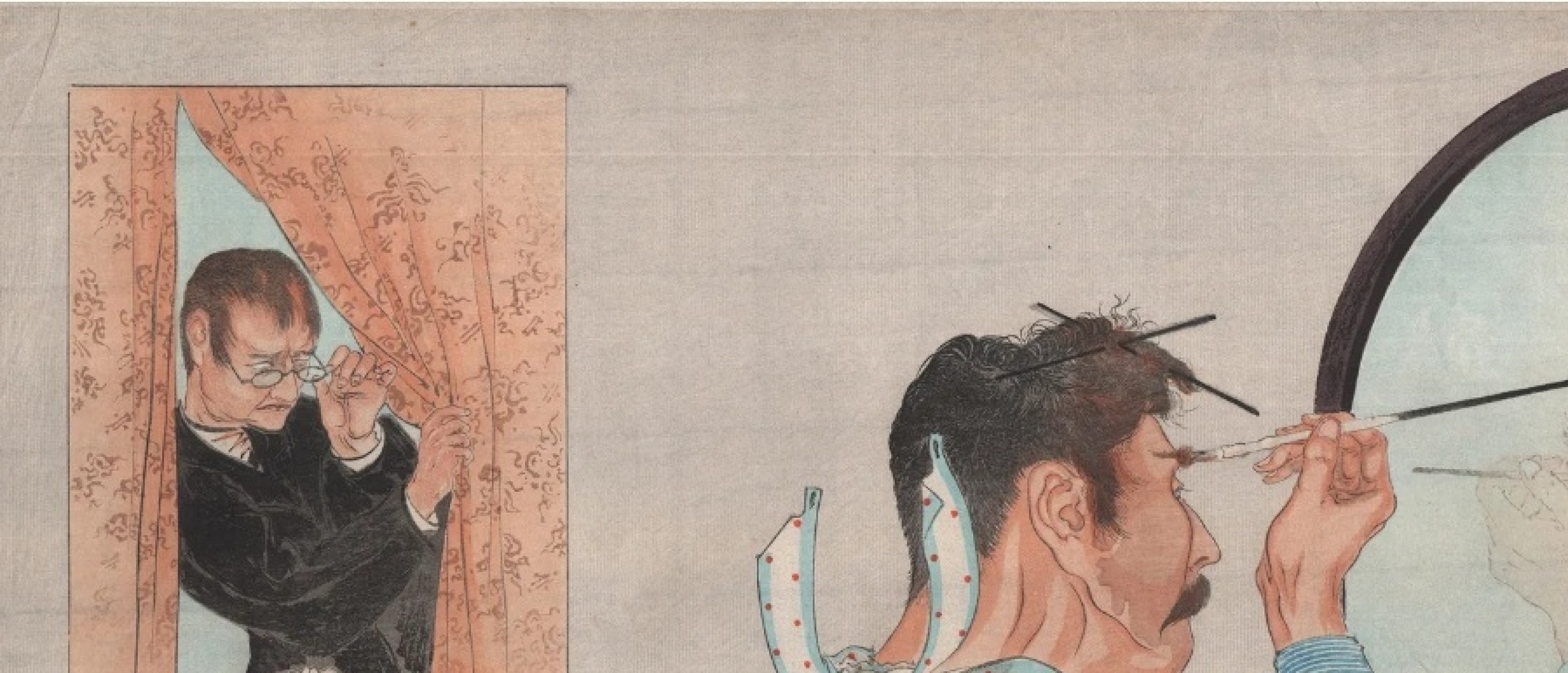

Fig.1 1926 Vintage poster by Charles Gesmar, featuring the famous aerialist and female impersonator, Barbette (born Vander Clyde)

Fig.2 1937 portrait of a young boy, Boris Snezhkovsky by Konstantin Somov, the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

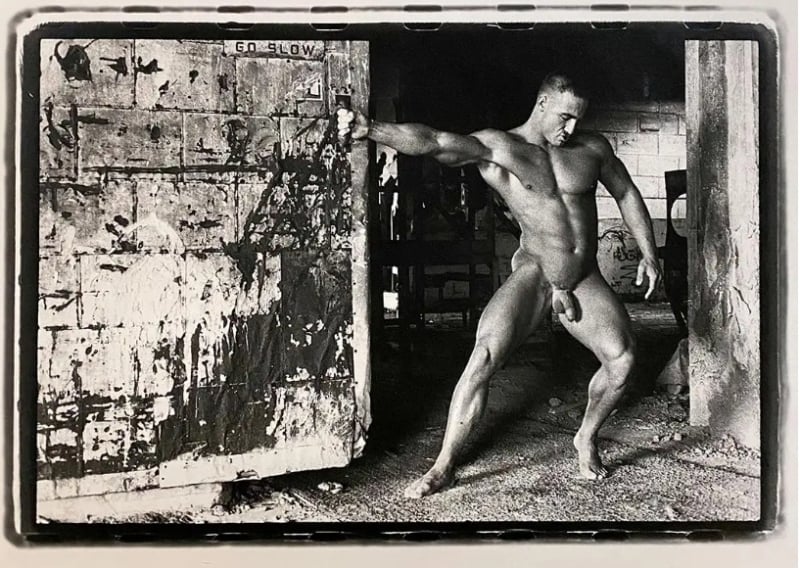

Fig.3 An He verströmt einen kraftvollen Duft wie ein Pferd, 1991. (Credits 1stdibs)

Fig.4 David di Michelangelo, marble, Florence, Galleria dell'Accademia, 1501-1504, uploaded by Marcus Obal, Wikimedia Commons.

Mythologies of Homoeroticism

Long before hashtags and Pride floats, desire between men had its gods, its rituals, its icons. Eros himself — the naughty archer, Aphrodite’s winged messenger — was hardly straight. He was part of a trinity of divine patrons of male-male love alongside Heracles (strength) and Hermes (eloquence). Apollo, the radiant sun god and master of music, had so many male lovers that he earned the title “champion of male love.” Same-sex desire wasn’t only tolerated in Greco-Roman myth, it was sanctified.

Cross-dressing, androgyny, the fluid play of gender identity: these weren’t late-twentieth-century inventions but sacred motifs in stories that Western culture would later recycle endlessly. Ganymede, abducted by Zeus in a homoerotic lightning storm; Hyacinthus, killed by a jealous wind but reborn as a flower; Hermaphroditus, neither boy nor girl but both. Today’s LGBTQ+ spectrum finds its shimmering prequel in these mythologies.

Plasma - Thanks A Lot But No Thanks

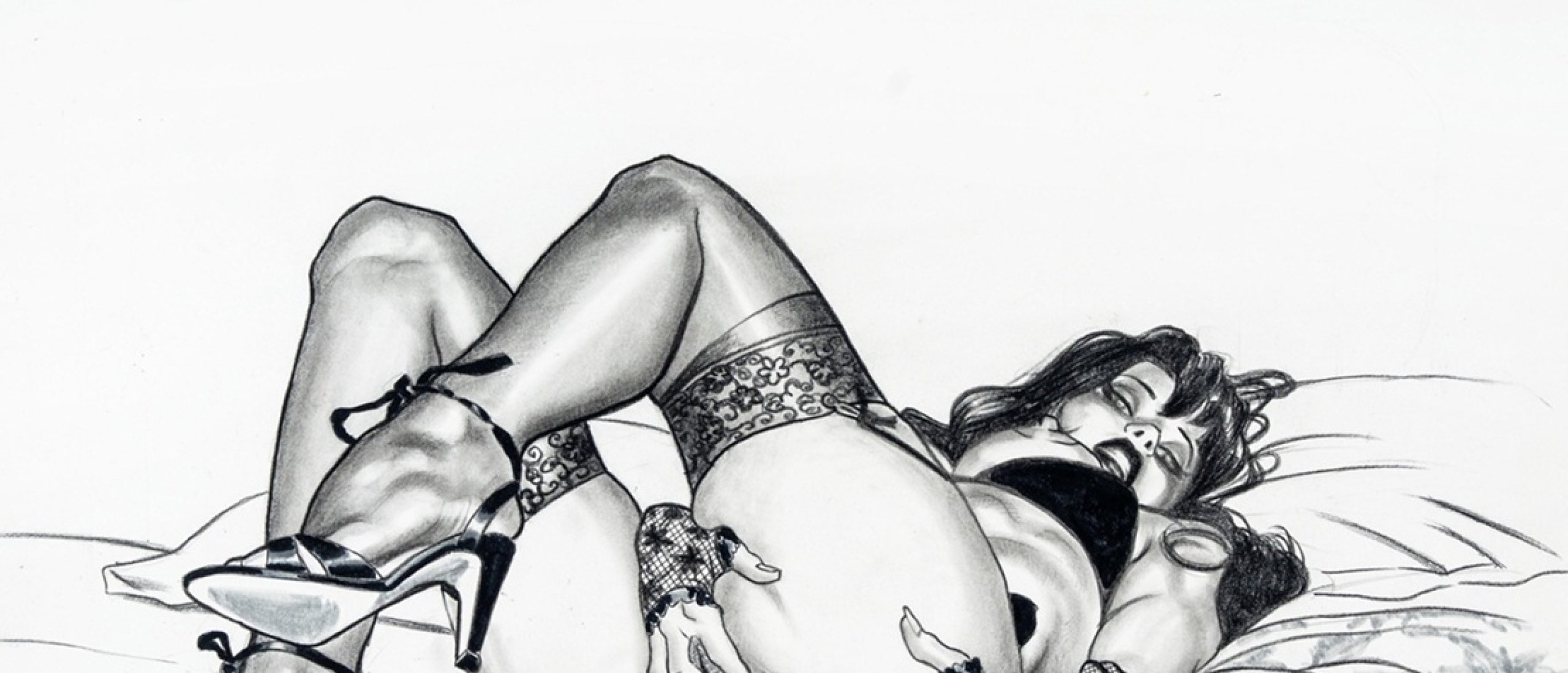

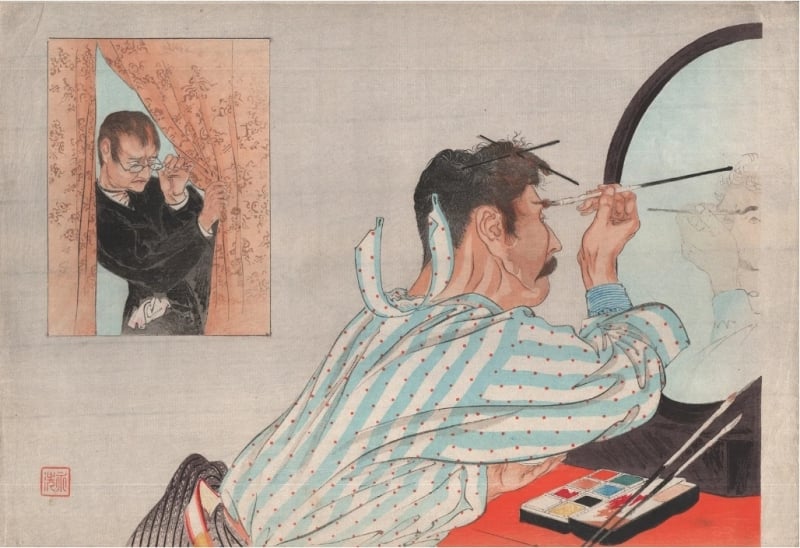

Fig.5 A woodblock print by Tomioka Eisen (c. 1906). Private collection (Courtesy Wrightwood 659)

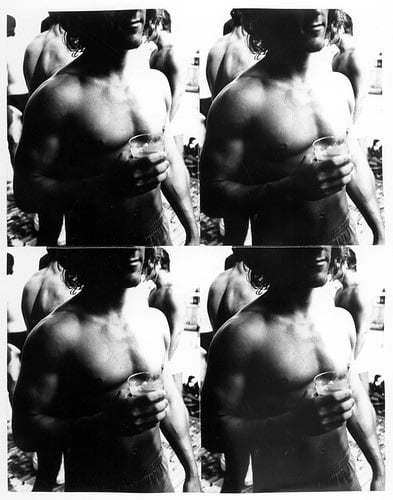

Fig.6 Andy Warhol, Young Man holding a glass, 1976-1986. Credits The Andy Warhol Foundation, (via Eye Magazine)

Fig.7 Another Saint Sebastian, 1636 by José de Ribera, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Michelangelo: Eros and Psyche, Body and Soul

Renaissance in Florence, marble dust in the air, and a fifty-something Michelangelo suddenly writes poems and sends erotic drawings to a beautiful Roman youth, Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. This was no secret crush. In 1532, Michelangelo described Cavalieri as “the light of the age, unique in the world.” His “Presentation Drawings” for the young man were unlike anything he had done before: not preparatory sketches, but finished works of intimate devotion, homoerotic love letters in chalk and ink.

Michelangelo had spent decades sculpting male bodies — David, heroic and naked, an eternal hymn to strength and beauty. But when he gave Cavalieri Ganymede carried aloft by an eagle, it was more than myth: it was Michelangelo announcing, in Renaissance code, “I love men.” His poems, widely circulated, even sung in salons, did not whisper but shout. Cavalieri himself showed the erotic drawings to the pope, who — far from scandalized — admired them.

Michelangelo could risk this Renaissance coming-out partly because genius was license. Artists were regarded as divine oddities, free to flout convention. And yet the struggle remained: Condivi, his biographer, tried to explain away Michelangelo’s passions as “chaste,” like Socrates. But the marble bodies and smudged sketches tell another story — one of desire sublimated, and sometimes not.

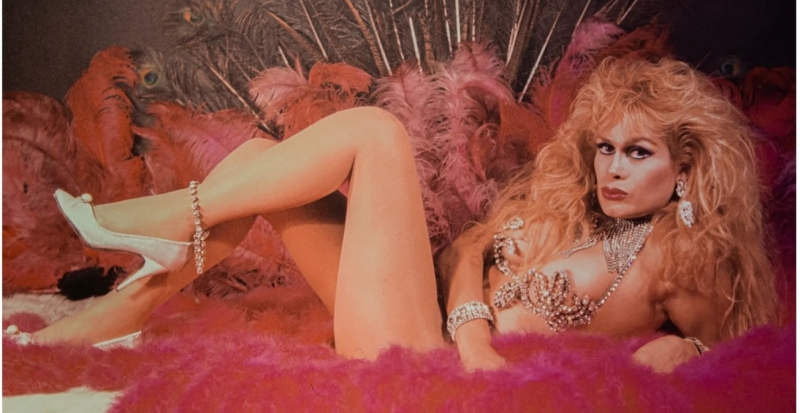

Fig.8 Antonella Rubens por Jesús Magaña (1995). Plasticidades Encarnadas - Exhibition of Trans Women’s Art in Mexico. Courtesy of Museo de Arte Transfemenino, Mexico City

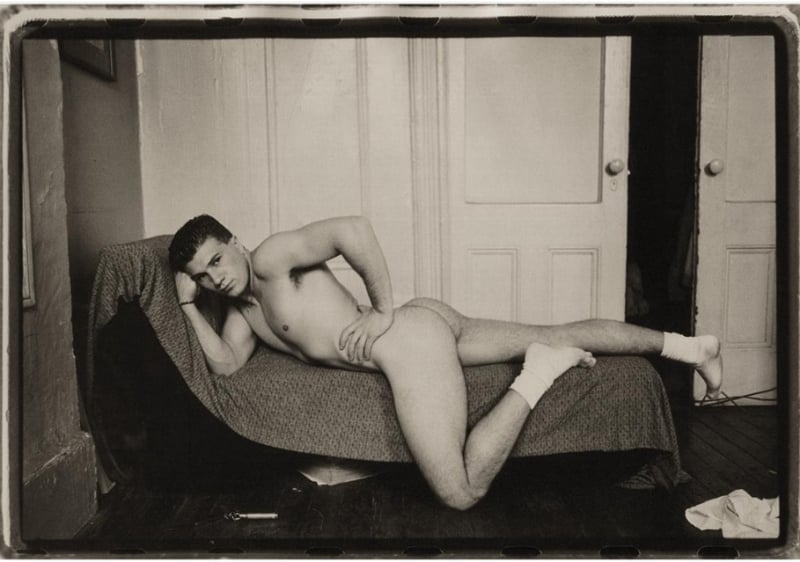

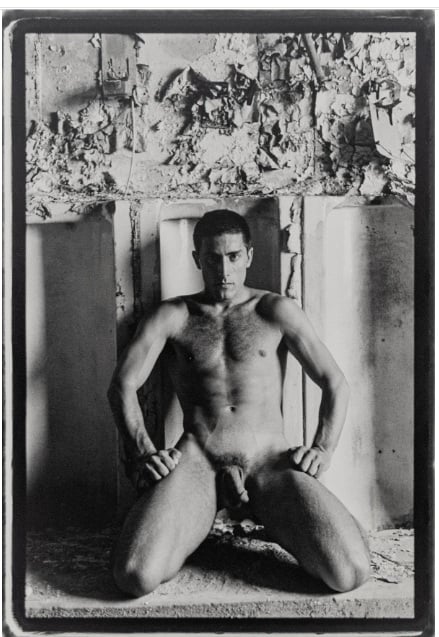

Fig.9 Bill Costa, The Apsara, NYC 1990. (Credits 1stdibs.)

Fig.10 Bill Costa, Unbenannt 1993. (Credits 1stdibs)

From Elisarion to Hirschfeld: The Birth of “Homosexuality”

Same-sex love, of course, always existed, never disappeared. What changed was the label. By the late 19th century, the word “homosexuality” had been coined, pathologized, politicized. Art became a sanctuary and a declaration.

Enter Elisàr von Kupffer, aristocrat, painter, self-made prophet. He rebranded himself as “Elisarion” and built a temple in Switzerland filled with kitsch visions of a genderless utopia. His “clear world” was populated by Aryan youths bathed in light, neither male nor female. It was both utopian and unsettling: a queer Midsommar, complete with fascist undertones. (Elisarion even wrote to Hitler. The Führer never replied.)

Meanwhile, in Berlin, Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science flourished. It was part clinic, part activist hub, part queer utopia — pioneering gender-affirming surgeries, cataloguing every nuance of sexual difference. When the Nazis came, they raided it, burned the research, and destroyed decades of fragile progress.

Drag queens, cabaret singers, artists fled or were silenced. History repeated: visibility, then backlash. Sound familiar? Trump’s America swapped drag shows for “groomer” panics, but the scapegoating logic is the same. Art, once again, became the refuge, the archive of difference.

Fig.11 Brassaï, Le bal des invertis au Magic-City, rue Cognac, 1932. Ferrotyped gelatin silver print on single weight paper. Credits Artsy

Become a Premium member and discover the kinky revelations behind the following captions:

- The Jungian Shadow: Desire and Its Demons

- Prieto, Baldwin, Wilde: Homoerotica Between the Wars

- Warhol, The Factory and Lou Reed’s Wild Side

- Leigh Bowery: Glitter, Shit, and the Performance of Decadence

- Men, Love, Punishment — and Liberation

- 56 additional pics and 4 videos

Click HERE for part IV (The Erotic Archivist) or HERE for the erotic drawings of "Sir Gay" Eisenstein, a pioneer of montage

Let us know your thoughts on this third part in the Eros/ Eroticon series in the comment box below..!!