In the current article, we pay attention to the series of erotic prints made by one of the most prominent engravers of the Renaissance period Agostino Carracci (1557-1602), whose erotic set ‘I Modi’ was a theme of our previous post.

Fig. 1. Self-portrait as a watchmaker (Wikipedia.org)

Homo Universalis

The case of Carracci gives us an example of the so-called Homo Universalis. Agostino Carracci originated not from a dynasty of artists and printmakers as we could expect. His father was a tailor. Moreover, Agostino was initially trained as a goldsmith but began to study painting after being persuaded by his cousin Ludovico Carracci. Together with the cousin and his minor brother Annibale Carracci, Agostino established the Accademia degli Incamminati (Academy of the Progressives) in Bologna, where he gave classes on the theory of arts. Since 1574, Agostino had been reproducing oeuvres of Tintoretto, Veronese, and Correggio in his engravings. Three artists together decorated Palazzo Fava and Palazzo Magnani in Bologna. In 1598, Agostino and Annibale also collaborated on the Farnese Gallery in Rome. The fresco cycle ‘The Loves of the Gods’ on the vault of Farnese Gallery had one of its’ sources in the Lascivie series earlier produced by Agostino.

Fig. 2. ‘The Loves of the Gods’ on the vault of the Farnese Gallery by Annibale Carracci (Wikipedia.org)

Lascivie

‘Lascivie’ (Lascivious) series consists of 15 prints on Biblical or mythological themes, unsigned and undated. Scholars date these prints between 1590 and 1595 because they were censured by Pope Clement VIII, who held his post from 1592 to 1602. In the book on the life of Carracci (published in 1678), Carlo Malvasia wrote that the publisher Rosigotti sold Agostino’s prints to people ‘who ought to have forbidden him to do this.’ Probably it was the members of the papal curia who bought these scabrous pictures. All authors writing on Agostino’s life and work try to justify the production of ‘Lascivie.’ They appeal to the fact that such a venture was profitable for the publishers, who valued Agostino’s works and competed with one another to get him. The erotic series was indeed sought after as the original plates were overused. Yet personality of the commissioner remains unknown.

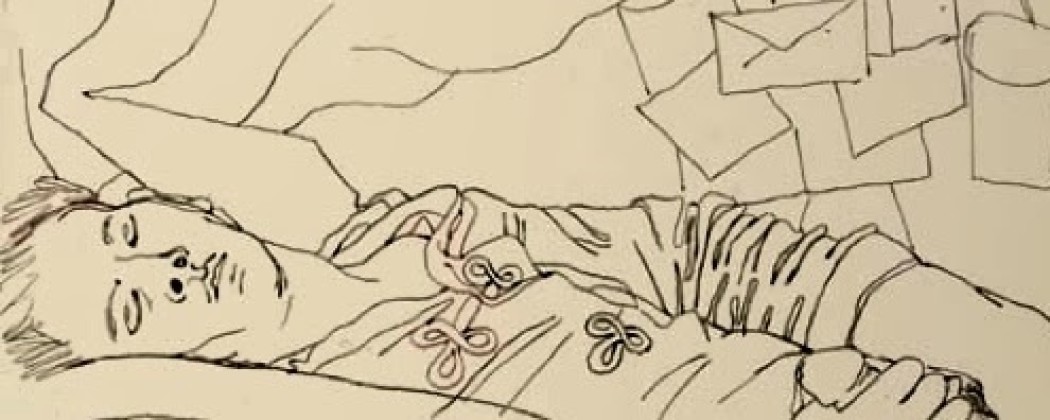

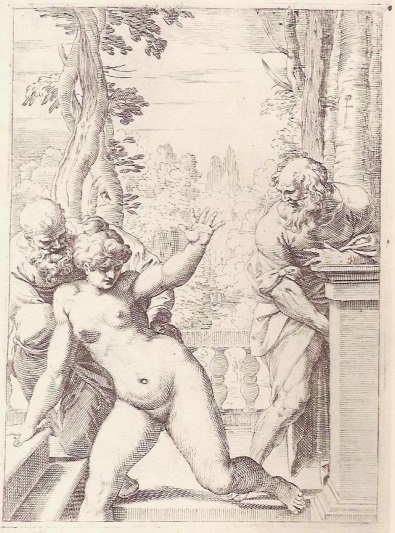

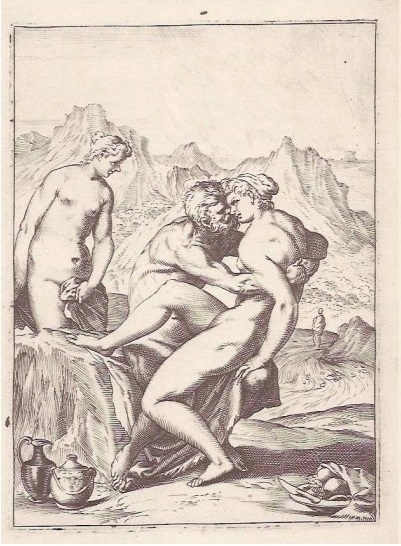

Susanna and the Elders

The Biblical plot, which is of great current interest in our harassment times, is represented by the first figure of ‘Lascivie.’ The salacious elders peeped at the voluptuous body of Susanna while she was bathing in the garden. Being aroused by her carnal beauty, they threatened her with an accusation of adultery with a stranger if she refused to copulate with them. Perpetrators were denounced by the Biblical hero Daniel.

Fig. 3. Susanna and the Elders (W. Eubanks. The Lascivie)

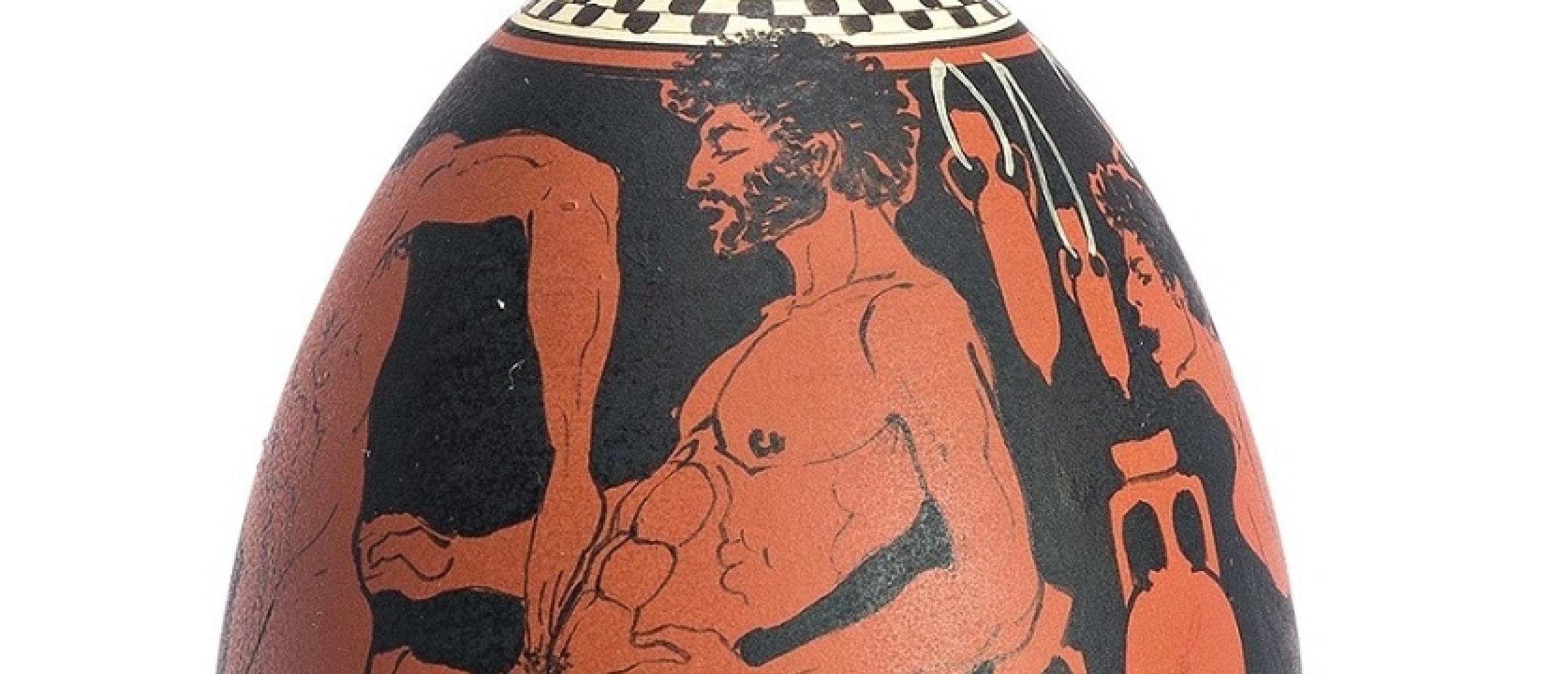

Lot and His Daughters

The second figure from the set actualizes another Biblical narrative that pertains to Lot’s family led by the angels out of destroyed Sodom. Angels forbade them to look back at the crushing town, but Lot’s wife violated this instruction and was turned to a salt pillar. When Lot dwelled with his daughters in a cave, they decided to lay with him thinking that there weren’t any men on the earth. So, being wined, unconscious Lot impregnated his offspring. Incest is often described in Bible, but the story of Lot’s daughters designates a change in Jewish rules. Levit books canceled incestuous marriages. Allegedly, this story demonstrates the superiority of Jews over Arabian nations, as Lot’s daughters gave ‘wicked’ birth to their ancestors. In Agostino’s engraving, daughters display their disgust but still seduce their father, as they are sure they have to do it. The figure of a man in the background indicates the pointlessness of the incestuous affair. Two vessels at the bottom of the picture symbolize the daughters as the receptacles of their father’s seed, while the knife on the bowl with fruits refers to penetration.

Fig. 4. Lot and his daughters (W. Eubanks. The Lascivie)

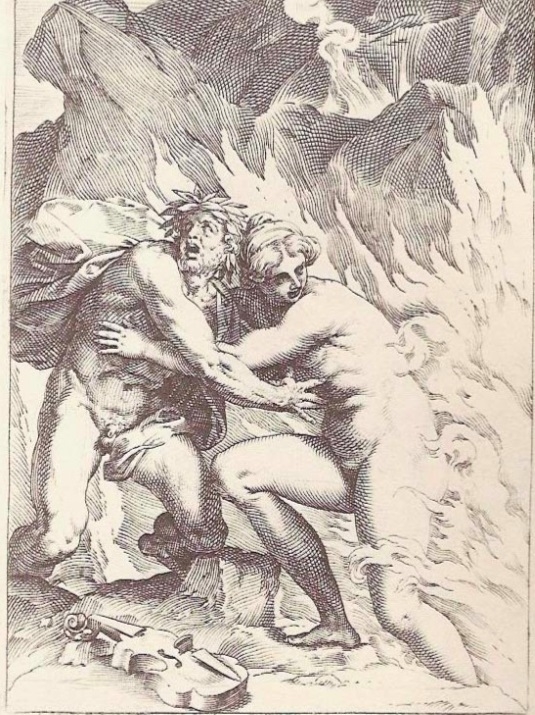

Orpheus and Eurydice

The third piece opens a sequence of mythological prints in the ‘Lascivie’ series. It’s a famous story of Orpheus and his beloved Eurydice. Agostino’s image depicts the moment of the second ‘death’ of Eurydice after Orpheus had looked back at her. It’s known that the legendary musician was in such great sorrow when Eurydice had passed that he traveled to Hades and persuaded him by his performance to let the woman he loved back to earth. The only stipulation was not to look at Eurydice on their way to the daylight. Orpheus couldn’t manage his curiosity and lost his love forever.

Fig. 5. Orpheus and Eurydice (W. Eubanks. The Lascivie)

Look Back and Look Away

The ‘Metamorphoses’ by Ovid reads: ‘Orpheus wished and prayed, in vain, to cross the Styx again, but the ferryman fended him off. Still, for seven days, he sat there by the shore, neglecting himself and not taking nourishment. Sorrow, troubled thought, and tears were his food. He took himself to lofty Mount Rhodope, and Haemus, swept by the winds, complaining that the gods of Erebus were cruel. Three times the sun had ended the year, in watery Pisces, and Orpheus had abstained from the love of women, either because things ended badly for him or because he had sworn to do so. Yet, many felt a desire to be joined with the poet, and many grieved at rejection. Indeed, he was the first of the Thracian people to transfer his love to young boys and enjoy their brief springtime and early flowering, this side of manhood.’ W. Eubanks suggests that, as Orpheus looks away from Eurydice, the print tells us not of the loss but of its’ consequences. Namely, of the musician’s further connection to pederasty.

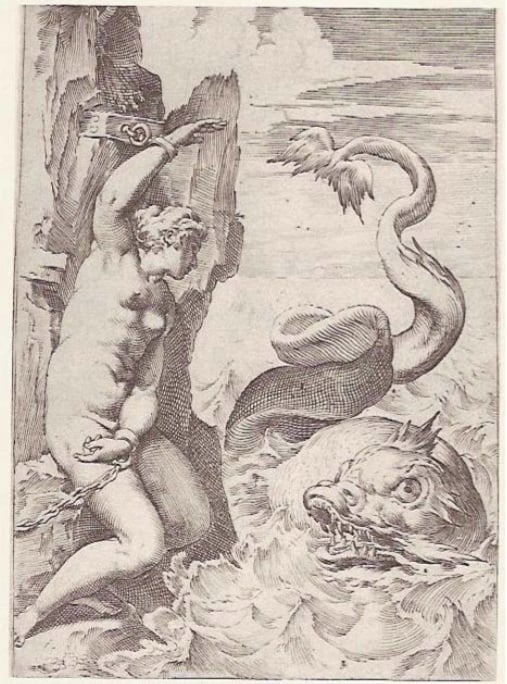

Andromeda

The fourth print depicts manacled Andromeda in front of the sea-monster. Andromeda became a victim of her mother’s vanity, who boasted that she was more beautiful than Nereides. Sea nymphs complained to Poseidon, and the latter sent the monster to the country where Andromeda lived. The oracle said that Andromeda must be sacrificed to the sea creature, and she was left on the rock, where Perseus rescued her. This print was a direct source for the painting by Spanish artist Juan Antonio de Frías y Escalante, created in the 1660s. The only difference between the two oeuvres lies in the excluded nudity in Escalante’s painting.

Fig. 6. Andromeda (W. Eubanks. The Lascivie)

Fig. 7. Andromeda by Juan Antonio de Frías y Escalante (Wikipedia.org)

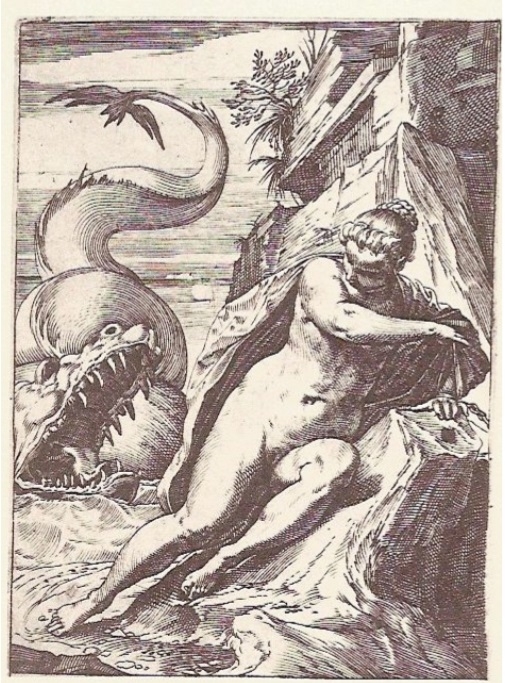

Hesione

The next print depicts a story similar to the previous one. Trojan princess Hesione (‘Asione,’ which meant Asian) was King Laomedon’s daughter and Priam’s sister. She was sacrificed to the monster sent by Apollo and Poseidon for not paying them the wage her father promised for building the walls of Troy. She was rescued by Heracles in exchange for the horses given to Laomedon by Zeus. Well, in exchange for a promise, as Laomedon predictably didn’t give the hero his reward.

Fig. 8. Hesione (W. Eubanks. The Lascivie)

Sources: Waverley W. Eubanks. The Lascivie: Agostino Carracci’s erotic prints as the sources for the Farnese Gallery vault. A Thesis for Master of Arts degree. Georgia. 2008; Wikipedia.org; bibliya-online.ru; ovid.lib.virginia.edu

Click HERE for an article on the loves of the Gods by Renaissance artist Guilio Bonasone….!!

Let us know your thoughts on Carracci’s sensual Renaissance prints in the comment box below….!!