Long before the emergence of cinema, 3D images already existed. The devices that created them were called stereoscopes. The first stereoscopes were invented in 1832 by Sir Charles Wheatstone. These devices consisted of a pair of mirrors at angles of 45 degrees concerning the users’ eyes, each one reflecting apparently identical images, but different about the small angle with which each one of them was produced.

Fig.1.

Fig.1.

Depth Perception

Wheatstone wanted to demonstrate how depth perception arises from our binocular condition, showing that when two images, simulating the left eye and right eye view of the same object, are presented, each eye sees only the image projected to it, so the brain will merge the two images and accept them as an image of a three-dimensional object. As the stereoscope was created before the advent of photography, drawings were used to simulate three-dimensionality.

Fig.2.

Fig.2.

David Brewster

Throughout the 19th century, different types of stereoscopes were created. In 1849, David Brewster invented the lenticular stereoscope, which consisted of using lenses to unite different images. As Brewster could not find anyone to manufacture his invention in England, he took it to France, where it was improved upon by Jules Duboscq.

Fig.3.

Fig.3.

250,000 Stereoscopes

From there, a 3D industry was born that produced more than 250,000 stereoscopes as well as the images intended for their use, known as stereoviews, stereo cards, stereo pairs or stereographs. With the advent of the photographic process, photographs began to be used on the device.

Fig.4.

Fig.4.

Inherently Obscene

As a device that provided the illusion of three-dimensionality from two juxtaposed images, the stereoscope was not limited to representing landscapes or rooms full of objects, in which the 3D effect was clearer. As Jonathan Cray observes: “The stereoscope as a means of representation was inherently obscene, in the most literal sense. It shattered the scenic relationship between viewer and object that was intrinsic to the fundamentally theatrical setup of the camera obscura.

Fig.5.

Fig.5.

Pornographic Imagery

The very functioning of the stereoscope depended, as indicated above, on the visual priority of the object closest to the viewer and on the absence of any mediation between eye and image. [..] It is no coincidence that the stereoscope became increasingly synonymous with erotic and pornographic imagery in the course of the nineteenth century. The very effects of tangibility that Wheatstone had sought from the beginning were quickly turned into a mass form of ocular possession” (CRARY, Jonathan. Techniques of the observer: on vision and modernity in the nineteenth century, p. 127).

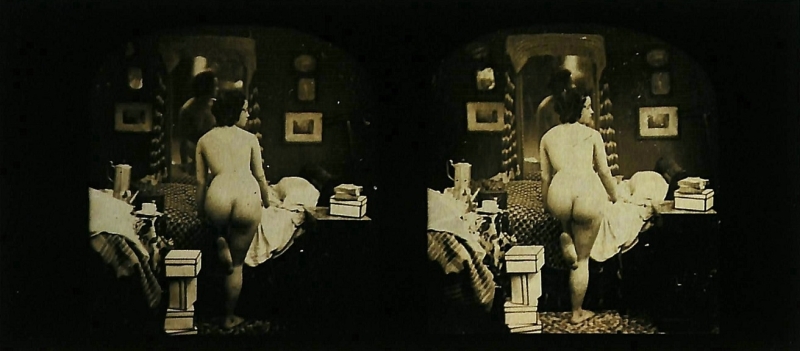

Fig.6.

Fig.6.

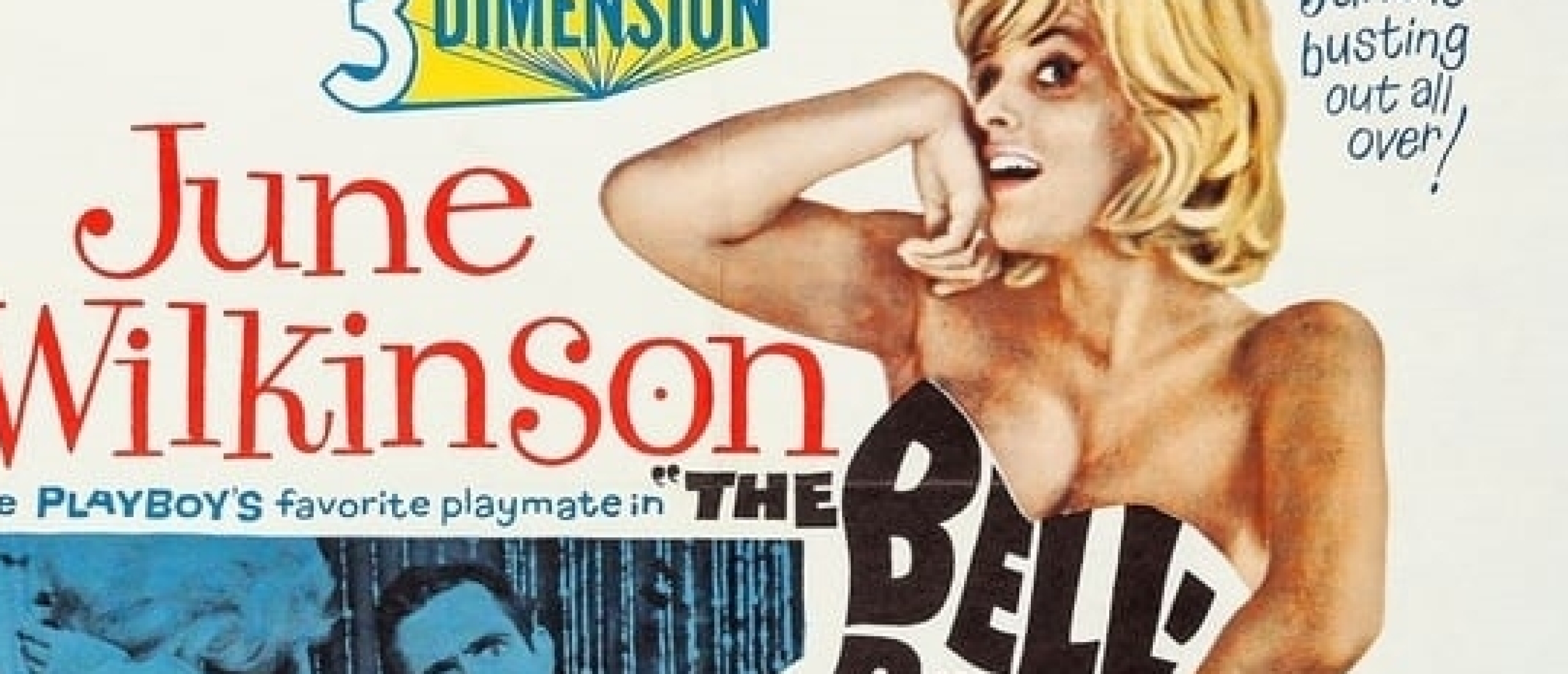

Female Nudes

In images of female nudes, this ocular possession is realized by the suggestion of movement conditioned by the relief offered by three-dimensionality. By having the sensation of seeing the objects and bodies “in front of” and “in the background of”, the image for the spectator appears as a sequence of receding planes, which gives the impression of the representation being in movement, located between a “before” and “after”.

Fig.7.

Fig.7.

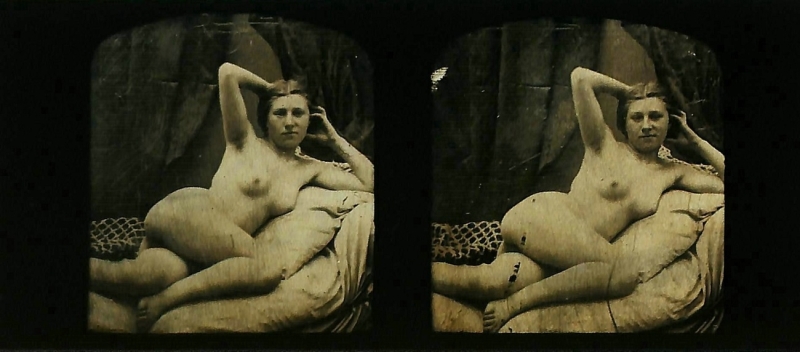

Mise en Scene In The Stereoscopic

This eagerness for the representation of a naked body in movement can be perceived in the stereoscopic images, when we see how the poses are constructed: women caressing their own feet, crossing their legs, contemplating themselves in front of the mirror, or having sex. The simulation of a domestic or natural environment serves as a setting for poses that exalt the sensuality of bodies as something spontaneous, often undisciplined, when compared to the nudes represented in classical-style paintings.

Fig.8.

Fig.8.

Fragmented Nudity

The presence of mirrors in the images produced for the stereoscope, while duplicating the body, sections it, adding its parts to others that make up the scenery, which is following the principles that govern the stereoscope, as Jonathan Crary explains: “Thus stereoscopic relief or depth has no unifYing logic or order. If perspective implied a homogeneous and potentially metric space, the stereoscope discloses a fundamentally disunified and aggregate field of disjunct elements.

Fig.9.

Fig.9.

Reveals the Body

Our eyes never traverse the image in a full apprehension of the three-dimensionality of the entire field, but in terms of a localized experience of separate areas” (CRARY, Jonathan. Techniques of the observer: on vision and modernity in the nineteenth century, p. 126). Although photography reveals the body in its completeness, its stereoscopic version fragments it.

Fig.10.

Fig.10.

In the Premium version of this article you can explore more on the revolutionary stereoscope and its portrayal of the nude, the relationship with shunga, 3D porn cinema and three times as much naughty (explicit) images.

Click HERE and check out the earliest Western pornographic daguerreotypes

Let us know what you think about the above article on stereoscopic erotic imagery in the comment box below...!!