In the second part (first part here) on the notorious geisha Sada Abe, we’ll take a look at her complex personality, penis envy and the audacious movie adaptation of her fatal love affair…

The Investigation of the Case In Prewar Japan

Though Japan is considered to be a secluded country, in the XXth century it followed European ideological trends. Eugenics, racial theory, Freudianism, and the views in spirit of Cesare Lombrozo were very popular among Japanese intellectuals. The murderess Sada Abe was treated as an example of a curious deviation caused by a physiological pathology. Among the reasons for her behavior, forensic doctors considered the crooked teeth, the menstruation, on which she was thoroughly examined, and her “hypersensuality.” The latter diagnosis gives us more information on the voyeuristic incline of the experts, as, according to Christine Marran, the witnesses, who were her former clients, were asked “how she was usually more interested in satisfying her own pleasure, how she would lick or suck the penis first sticking it in and then pulling it out, how she would lose her breath after orgasm, or how she was “ten times” more sensitive than usual women to the degree that her eyes would even change color when she was sexually excited.” The tragicomic extent of physiological obscurity of Sada Abe and her clients becomes obvious in the confession of the male who said that he thought she was ill because she was wet before sex. Abe replied to him that she had consulted a doctor who told her she just got aroused easily. Her bizarre attempts to erect the separated member can be regarded in this context both as a deviation and as an outcome of her weird innocence. The council of forensic doctors and investigators, however, didn’t pay attention to Abe having been raped at the age of 15. They didn’t take into account that she was sold to the locked geisha house against her will and that she consequently failed to have a healthy relationship with men who considered her a playtoy, as mentions Marran. We can add that this enormous love for Ishida probably had its’ roots in him treating her respectfully. As was mentioned above, speaking of Ishida, she emphasized his desire to please her, which she founded much better than the size of male genitalia. Paradoxically enough, it’s not fascism or social violence, but it’s brief sight of love and affection in the hostile environment that eventually transforms you into an impossible monster.

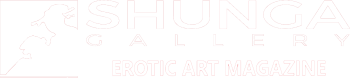

Fig. 17. The couple in the rain (In the Realm of the Senses, allpostersimages.com)

The Image of Sada Abe in Postwar Japan

Where science stops, art emerges. In the prewar era, Sada Abe was treated only as a patient. Her figure was studied through the prism of Freudian statements or issues of heredity. In the postwar time, a different approach appeared. Writers and filmmakers began reflecting upon Abe and Ishida’s relationships in connection with the social and political context of that time. Disobedient Abe becomes an enfant terrible, chaotic Yin force, which opposites the patriarchic Yan society meeting fascism. Masochistically resigning himself to the woman he loves, Ishida grows into a symbol of a desperate protest against the system. Their two-week trip and the quench for heaven pleasures are seen as an attempt to escape modern Japan turning itself into hell on the earth.

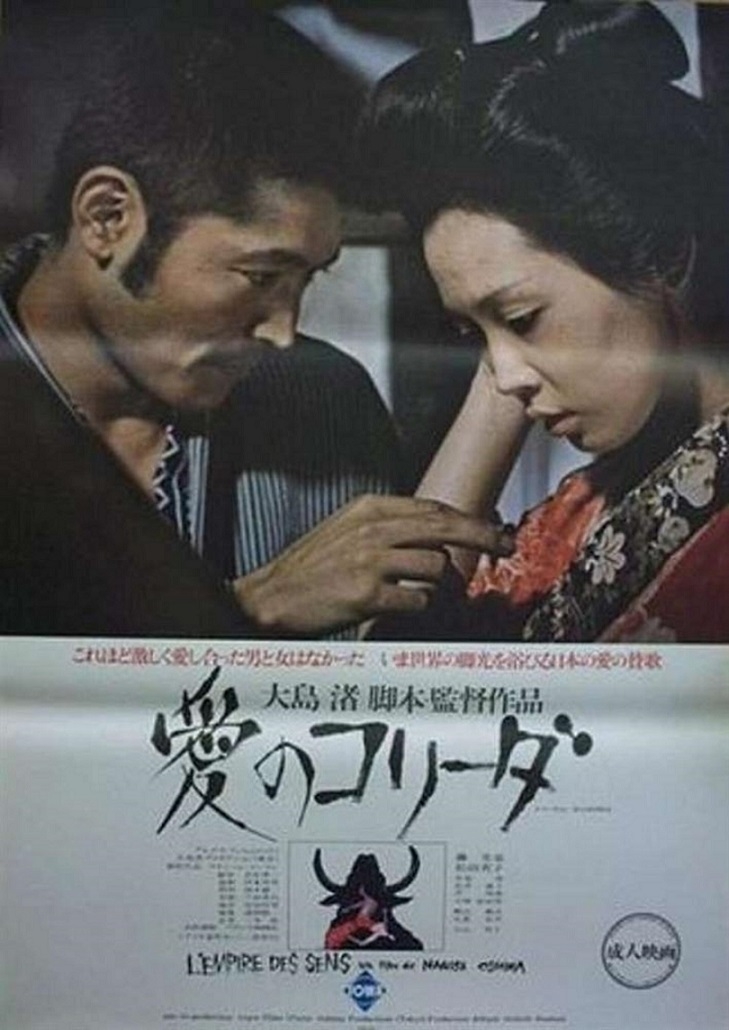

Fig. 18. “In the Realm of the Senses”, poster (8showbiz.com)

In the Realm of the Senses

The story has many adaptations, but we’ll talk about the most reckless one. In the Realm of the Senses (Ai no korīda, Bullfight of Love, 1976) is a film directed by Nagisa Ōshima with Eiko Matsuda as Sada Abe and Tatsuya Fuji as Kichizō Ishida. Interestingly enough, the film contains so many unsimulated sex scenes that a Wikipedia article defines it as a “pornographic art film,” however, people always avoid confusing these terms. Constant sexual activity of the main characters and depiction of Japanese realia (e. g. the harsh scene of kamuro’s defloration), yet the meditative spirit of some scenes involving Japanese landscapes make this movie a series of shunga pictures came alive.

Fig. 19. Eiko Matsuda and Tatsuya Fuji with Nagisa Ōshima (pinterest.com)

Fig. 20. Eiko Matsuda and Tatsuya Fuji with Nagisa Ōshima (pinterest.com)

Nothing Like the Sun

Searching for info about this movie, I’ve stumbled across a negative reaction, which allowed me to speculate on the differences between this film and pornography. The comment states that this film is nothing more than a porno movie because it’s not aesthetically perfect (the reviewer means unappealing sex scenes and the emphasizing of the physiological side of human love and life). The author claims that ugly, clumsy sex equals pornography, the movie is awful and disturbing, etc., etc. While reading this, I kept in my mind Betty Dodson’s utterance that, in fact, it is pornography that does make sex look appealing: beautiful girls with their gorgeous makeup and big breasts and glamorous bodies interact with each other or with sporty handsome boys, whose genitalia are always huge. They do it in impossible acrobatic poses somewhere on the firm kitchen table, which is hardly possible again, but their faked orgasms let us think that they found the most comfortable way to make love ever. The tale is ruined when you discover that your partner’s breast or cock is too small/too big/too average, their smell is not pure pheromones, and kama sutra poses are hardly manageable since you’re not athletes. So, what makes this film the art is its’ obvious anti-esthetic (which is still aesthetic) comparable to the famous 130th sonnet by Shakespeare “My mistress‘ eyes are nothing like the sun”. In “Romeo and Juliet” play, Romeo’s feelings for Juliette also opposite fake courteous fashion, which his previous relationship with Rosaline was.

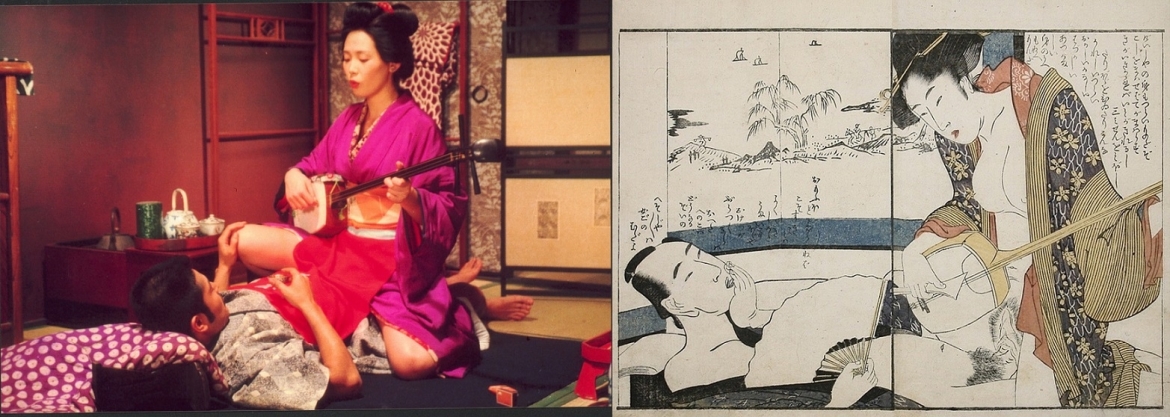

Fig. 21. Left: In the Realm of the Senses, Ishida with Abe playing the shamisen on top. Right: Utamaro, singing geisha

Fig. 22. Abe performing fellatio.

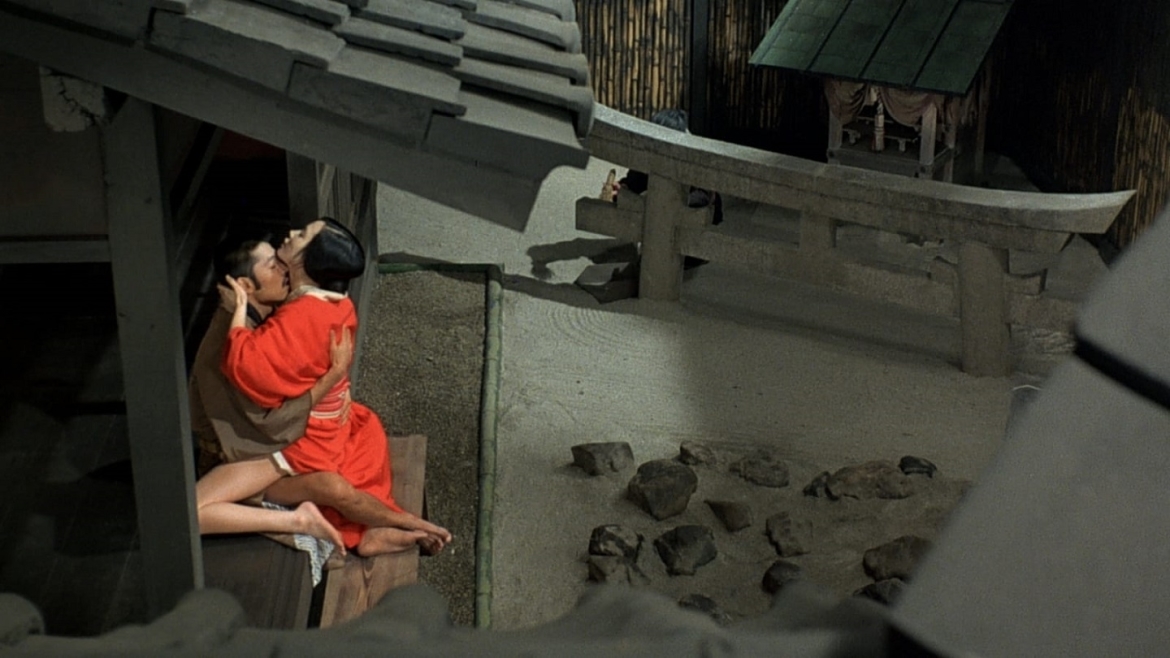

Fig. 23. The lovers having sex outside.

Fig. 24. Kamuro being deflorated by geishas.

Japanese Actionism

The adherence of the heroes to each other’s bodies is especially accentuated. When the maidservant enters the room saying, “We must clean it up. There’s a smell,” Abe replies aggressively, “It’s our smell!”. When the sensei, her client, whose prototype was Gorō Ōmiya, meets her the day before the murder, he tells her that she smells “like a dead rat.” Ishida ardently loves her body too. During their trip to another teahouse, Abe tells him in a saddened voice that she’s on her period. Ishida says that it doesn’t matter and, having inserted fingers in her vagina, tastes the menstrual blood as proof to his words. Another memorable scene is the dinner when Abe, witnessed by a geisha, puts the food in the vagina and then feeds Ishida. The lover accepts this game and putting a little egg inside Abe makes her “lay it as a hen does.” A naive viewer would find it disgusting. A sophisticated one would surprisingly recognize here performances of the first European actionists (we’ve already published the article on the actionist Hermann Nitsch). The main instrument of their art is the body and all its’ liquids: blood, piss, sperm, vaginal secretion. The egg scene evokes the performance by the Austrian artist Otto Mühl (1925-2013) that happened in the 1960s. During this action, the broken egg was dripped into the artist’s mouth from the menstruating vagina. Another thing to mention is the protest message of the actionists. Like Abe and Ishida on the screen, they rejected the world torn apart by the war. The final posthumous mutilation in the movie becomes an artistic act as well. The penis is not only the source of Abe’s pleasure but also a symbol of a militarized society. While severing it, Abe of 1976 liberates Japan from its’ violent past.

Fig. 25. Ishida inserts an egg into Abe’s vagina.

Fig. 26. Abe lies the egg witnessed by a geisha.

Fig. 27. Separated Ishida’s member.

Fig. 28. Ishida’s testicles.

Intentional Suicide

The behavior of Ishida contrasts with Abe’s actions at the end of the movie. While her smell is being characterized as one of a dead rat, he returns to his restaurant. He does it not to see his wife, as it may seem, but to wash the body. The scene showing him going alone towards a group of soldiers is the key to his final fate. Along with Abe contemplating the crime, he contemplates what we can call suicide. When he washes, he does it for the last time, actually, he washes the corpse. When he suggests strangling without a stop, he barely jokes. This way, the story of Abe and Ishida transforms into a cooperated cathartic ritual similar to European happenings.

Fig. 29. Ishida meeting soldiers.

Transgressive Sensuality

The adaptation of the Abe Sada incident is another example of the transgressive relationship tracing back to the medieval novel about Tristan and Isolde. The heroes, whose love contradicts the social norms, isolate themselves in the uninhabited territory (in the novel, they were hiding in the woods). Ōshima characters isolate themselves in the teahouses (the locked establishments, where Abe was imprisoned in her youth, become their own unassailable fortresses). Both the lovers’ seclusion and the sadomasochistic nature of their relationship put this film in a row with the scandalous oeuvre “The Night Porter” shot by Liliana Cavani in 1974. The film tells of the formal lovers, Nazi torturer Maximilian and the former prisoner of the concentration camp Lucia, accidentally meeting in the Austrian inn in 1957. Their love was unnaturally provoked by the infernal surrounding. The war with a biblical scope was a scene where they played their “biblical story,” as Max describes it: he gave Lucia the head of her inmate, who bullied her, and thus she became his personal Salome. Their connection is rooted in the terrifying narrative that is no longer told, but they can’t refuse their past: biblical stories cannot pass as far as they are eternal. The story of Abe and Ishida doesn’t have a direct source or a pre-written scenario. Now it’s timeless itself.

Fig. 30. Abe strangling Ishida with her obi sash.

Sources: Wikipedia.org; Christine Marran. So Bad She’s Good: The Masochist’s Heroine in

Postwar Japan, Abe Sada. Bad girls of Japan / edited by Laura Miller and Jan Bardsley. 2005.

Click HERE for one of the most gruesome shunga designs produced in the 19th century…!!

Did you enjoy our two-part article sequence on Abe Sada? Leave your reaction in the comment box below…!!