Suzuki Harunobu (1725?-70) is often cited as one of the great ukiyo-e print artists, but the magnitude of his reputation as an artist is not matched by the depth of information about the man himself. His death date is one of the few certainties; he died in 1770, perhaps at the age of forty-five. He lived in Edo in the Yonezawa-cho district near the Ryogoku Bridge, and he was probably a pupil of Nishimura Shigenaga (1697?-1756).

‘Couple watching waterlelies‘ from the series ‘Eight Fashionable Views of Edo: Vespers Bedmate at Ueno (Furyu Edo Hyakkei: Ueno no bansho)’ Suzuki Harunobu. Date: c.1769.

Egoyomi (Calendar print)

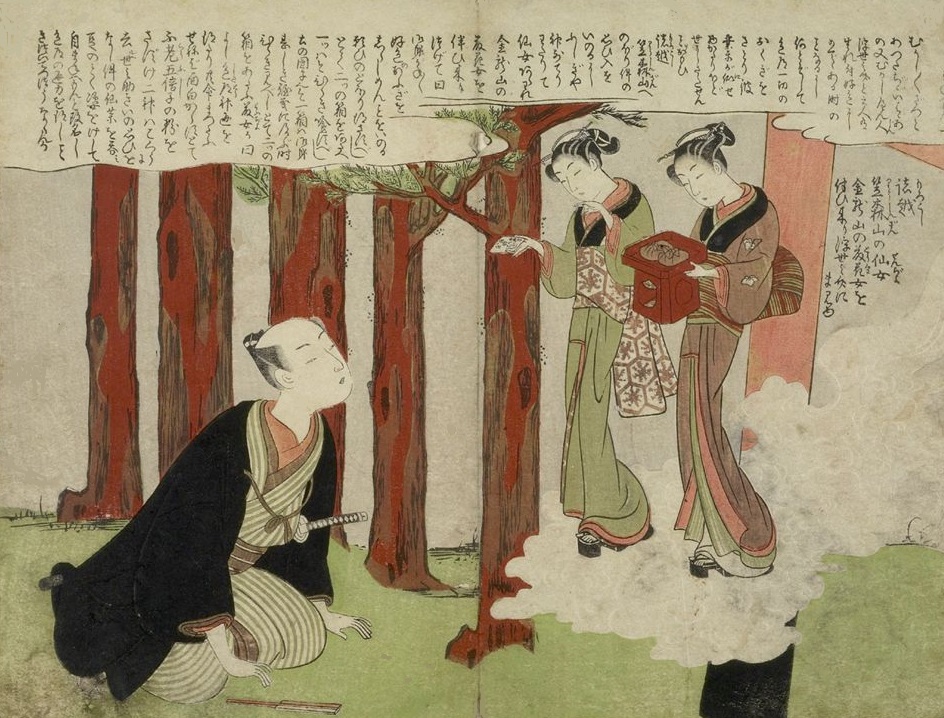

Up until around 1765, woodblock prints were coloured either by hand or woodblock printed with a limited palette as seen in benizuri-e, so called because of the dominant use of safflower red (beni). Harunobu too designed a number of benizuri-e. It was also around this time, in 1764-65, that the samurai bannermen (hatamoto) Okubo Jinshiro Tadanobu (1722-1777) and fellow hatamoto Abe Hachinojo Masahiro (d.1777) commissioned Harunobu to design privately published prints for exchange parties of egoyomi (pictorial calendar prints) held at the New Year.

Commercial

No expense seems to have been spared in their production, and possibly with the assistance of Harunobu’s neighbour, the scholar and author Hiraga Gennai (1728-79), they were printed using a full range of colours. Full-colour printing, as spawned by these privately issued egoyomi, would soon be adopted for commercially produced prints. These commercial full-colour prints would become known as nishiki-e, or ‘brocade pictures’, so named because of their association with colourful brocade silk (nishiki).

Lusty Maneemon

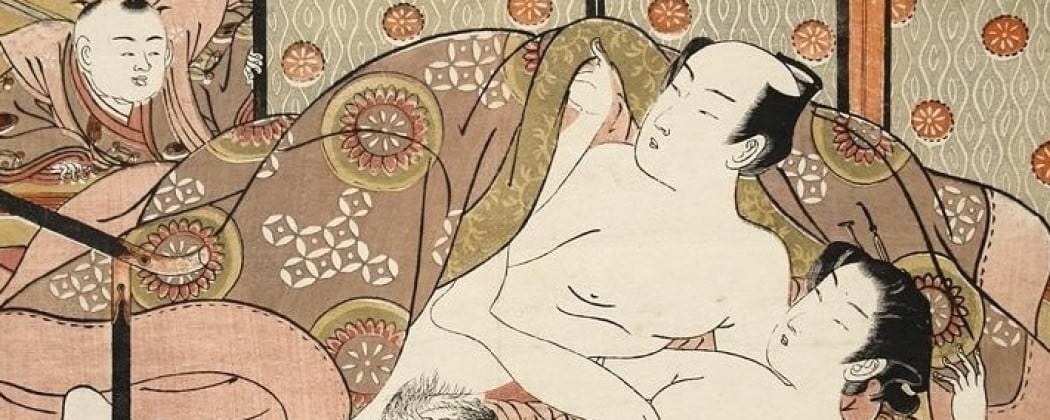

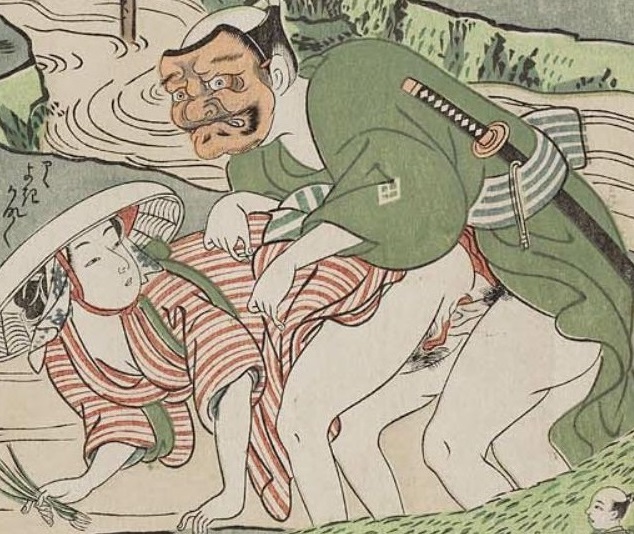

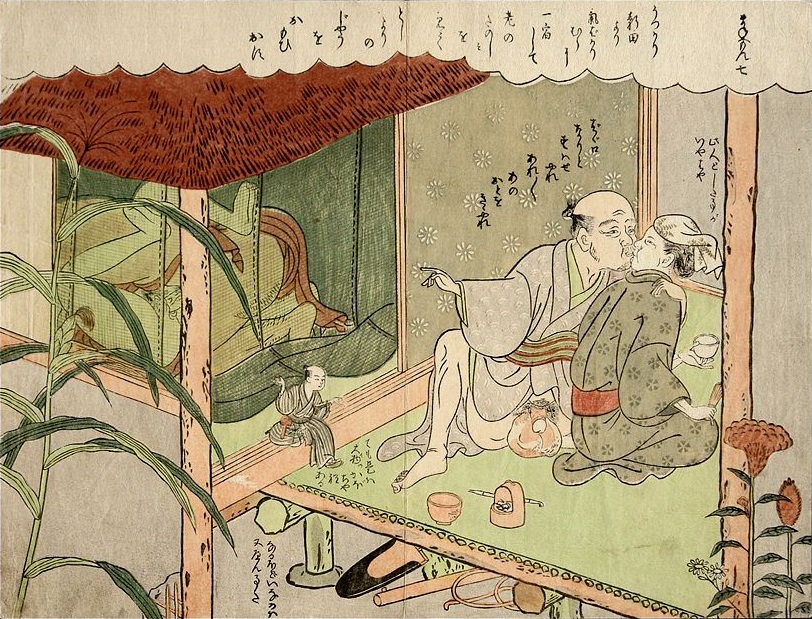

Harunobu created a sizeable body of work in the last six years of his life. Virtually all his non-erotic prints were in the upright chuban format (c.265 x 195 mm), whereas his numerous erotic prints were horizontal chuban. His most famous albums and series of chuban prints are The Spell of Amorous Love (Ebshoku koi no urakata, c.1768-70); Eight Fashionable Parlour Views (Furyu zashiki hakkei, c.1768); Eight Fashionable Views of Edo (Furyu Edo hakkei, c.1769); and The Fashionable Lusty Maneemon, 1770, which consists of two albums of twelve prints.

‘Old and young couple‘ from the series ‘The Fashionable Lusty Maneemon‘ by Suzuki Harunobu. Date: c.1770.

Robust

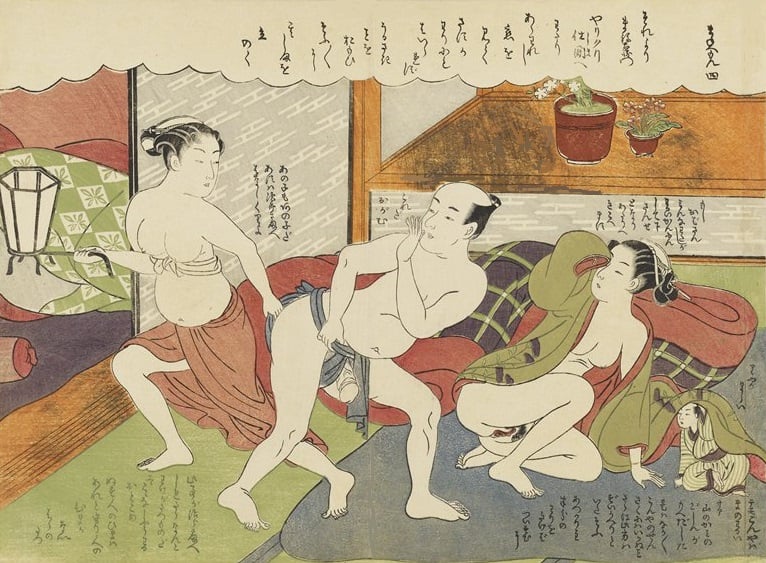

Harunobu was a prolific artist, as was his pupil Isoda Koryusai (1735-1790). Born of samurai stock and associated with Tsuchiya family, Koryusai moved to Edo following the death of his lord and settled in the Yagenbori district, near Ryogoku Bridge. He designed chuban prints, numerous hashira-e (‘pillar pictures’) and a substantial number of shunga. Koryusai’s early work was faithful to the style of his teacher Harunobu, but his female forms became more robust once he began working in the larger oban format in shunga appeared with Koryusai’s series Twelve Holds of Love (Shikido torikumi juniban, c.1775-77) and it is the greatest contribution to the development of shunga.

1,000 Shunga Designs

It is probably correct to say that the enlarged format offered by the oban resulted in a focus on genitalia, and its characteristic distortion in shunga after Koryusai’s time has received so much attention and humorous comment. Koryusai’s oeuvre is now well documented: he produced at least fifty series and illustrated books, the majority being nishiki-e. In his relatively short career Koryusai must have produced around 1,000 shunga designs, divided between prints that were published individually or as albums and book illustrations.

Corruption

Government censorship was apparently lax during Harunobu and Koryusai’s period of activity (1765-1780), and their careers overlapped with the tenure of Grand Chamberlain Tanuma Okitsugu (1719-1788). At the height of Tanuma’s influence at the shogunal court, his policies seem to have condoned corruption and turned a blind eye to luxurious display of wealth and pleasure. As a result, sumptuary laws and other edicts is evidenced in the works of both Harunobu and Koryusai: their signatures appear regularly, often positioned clearly within the frame of a screen or sliding door. Surprisingly, some of the same designs by both Harunobu and Koryusai exist with and without signatures.

Expensive

Hockley asserts that ‘as was the practice at the time, Koryusai’s shunga were issued in album or book form’. It is quite possible that prints were first produced as individual designs, just as with other serial graphics. They were later placed in albums to which an introduction or preface was added. The absence of centrefolds – creases resulting from works being in albums – in some of Harunobu and Koryusai’s shunga further supports the thesis that individual prints were produced and sold individually.

Also noteworthy is the fact that such an expensive item as the Maneemon album was released in a sizable edition. We know that the print run was sizeable because of the obvious wear to the blocks, as evinced in the quality of printing and the traces of shrinkage. This demonstrates that the sale of prints was not significantly impeded by restricitons set down by censorship laws and that commercial considerations even in these early days of printmaking were not inconsequential.

In the upcoming articles we’ll examine some of the greatest European artists of the nineteenth century who were influenced by shunga. The first will be Auguste Rodin, who is famous for his sculpture The Thinker.

Click here for the most comprehensive online introduction to shunga…!

The prints in this article are for sale in our shunga gallery!

Source: ‘Japanese Erotic Prints, Shunga by Harunobu & Koryusai‘ by Inge Klompmakers

Who is your among your favorite ukiyo-e artists? Let me know your thoughts!